阿公的圓桌: Braised Tofu of My Heart

plus a review of A-Gong's Table, Vegan Recipes from a Taiwanese Home and signed copies

This is Yun Hai Taiwan Stories, a newsletter about Taiwanese food and culture by Lisa Cheng Smith 鄭衍莉, founder of Yun Hai. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, sign up here.

I’ve lamented in the past that the recipes that “make it out” of Taiwan to be canonized in the English language tend to be the ‘charismatic megafauna’ of the cuisine—the popular attractions; the crowd-pleasers; the stops on the sightseeing bus. Full of symbolic meaning and charm, but overshadowing, as individual superstars, the nuance of the ecosystem (cuisine) as a whole. You know them, you love them, and I do too: popcorn chicken, beef noodle soup, lu rou fan, sesame noodles, and etc. I delight in preparing these dishes, but struggle to connect the dots between them when trying to incorporate Taiwanese culinary practices in my day-to-day.

The landscape is changing: we’ve been blessed by several Taiwanese cookbooks in the past few years, spurred on by a new wave of Taiwanese cooking in America and a growing awareness of Taiwan in the mind and conscience of the West. Among these are the exquisite, voice-y tomes from Taiwanese-American eatery Win Son and British-Taiwanese favorite Bao London. Frankie Gaw came out with First Generation, incorporating iconic American food into Taiwanese classics. The Taiwanese American Citizens League reissued Homestyle Taiwanese Cooking, a cult-status collection put together by their community. And, the journalistic Made in Taiwan: Recipes and Stories from the Island Nation, by Clarissa Wei, is a survey of Taiwanese food as a cuisine in its own right, led by local knowledge.

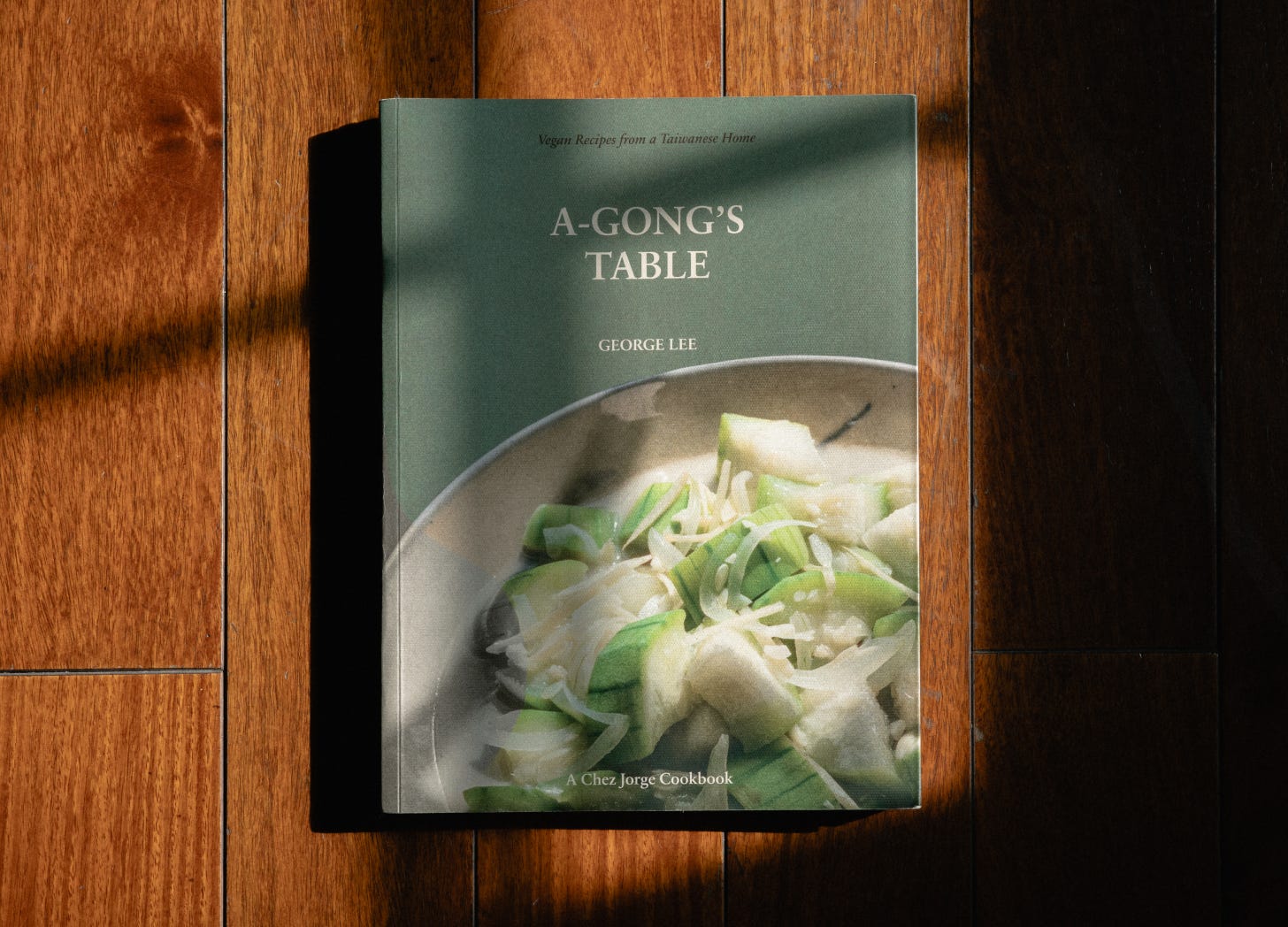

Today, I have the pleasure of announcing a new addition to the line up: A-Gong’s Table, Vegan Recipes from a Taiwanese Home. Written by George Lee (or Chez Jorge) over two years in Taiwan, this book is a tender and powerful exploration of personal memory and plant-based foodways. To me, it signals a turning point in English-language Taiwanese food writing. George is free to start from a place more deeply enmeshed in the cuisine and explore a niche topic: Taiwanese vegetarianism. For example, instead of explaining beef noodle soup, he explains that his grandmother has never eaten beef in her life; that the stigma around beef was lifted in Taiwan only relatively recently.

We’re so proud to offer this book in our online and brick-and-mortar shops. We’d be throwing a party, but George is in Taiwan and unavailable for book events until later this year. In lieu of hosting him at our shop, we've worked with his publisher, Ten Speed Press, to secure a limited quantity of signed copies. These are available exclusively at Yun Hai, both online and in-store. We’re also offering a bundle featuring ingredients mentioned in the text: Organic Lion’s Mane Mushrooms (grown in Taiwan) and Wu Yin Taiwanese Black Vinegar.

Finally, don’t miss out on our book giveaway—scroll all the way to the bottom for details.

One of the most memorable meals of my life was a simple cup of soy-braised pressed tofu (dougan 豆乾) and a bottle of plum tea at the vegetarian snack bar of Xiangde Buddhist Temple 祥德寺 in Taroko Gorge National Park.

The sun was shining, the sky was bright blue, and it was New Year’s Day. We had crossed the red Pudu Suspension Bridge 太魯閣普渡橋 on foot and climbed up the long stairway to the temple. Halfway up, we came to the temple's snack station, which sells vegetarian foods to the general public to benefit the monastery. On the menu were vegetarian noodle soups, braised dougan, plum juice, and Taiwanese herbal tea. They also offered Toon pancake 香椿抓餅, made from the tender shoots of the Chinese Toon tree, which have an oniony taste that stands in for the scallions Buddhists aren’t permitted to eat, and lotus leaf wrapped rice.

(Note: Xiangde temple is located in one of the areas in Taiwan hardest hit by the earthquake in Hualien earlier this month. Several people lost their lives in Taroko National Park and over 600 people were stranded for several days, including 12 monks at Xiangde Temple. Our hearts are with all who have suffered during the earthquake and its aftermath. Taroko National Park, not to mention the temple snack bar, are still closed following the earthquake; neighboring Hualien is rebuilding. We’ll be sharing ways to help soon.)

We ordered the tofu and sour plum drink. The dougan was tender and warm, served with a spoonful of fermented chili sauce and eaten with a skewer. The spiced flavors and comforting texture contrasted with the clear mountain air and searingly bright sunshine. In response, the ice cold plum juice reflected the crispness of the mountain atmosphere: tangy, bright, and the color of jasper.

We learned from the attending monk that the tofu was made on site, the plums harvested from a grove nearby, and the mountain’s natural spring water used for both the tea and the braise. It made sense that local ingredients would be so fresh and sharp. But, looking back now, I think the distinctiveness of the food had just as much to do with the preparation, carried out with kind intentions and ascetic precision.

After our meal, we continued up the path to the main temple, where we took in the beautiful vistas of the gorge and the bridges, perceived the extraordinary cleanliness throughout the grounds (I have video evidence of my husband marveling, “the floor is SO clean”), absorbed the transcendent chanting of the Buddhist monks, and were completely refreshed in body and spirit. On our way out, I purchased an electronic chant-box from the gift store, featuring recordings from the temple. I revisit it from time to time and find myself lifted.

It’s this memory that George Lee’s new book, A-Gong’s Table: Vegan Recipes from a Taiwanese Home, has evoked for me. This book explores veganism through the lens of Taiwanese food, with a focus on the Buddhist vegetarian practices he was exposed to after the passing of his A-Gong (grandfather). The first time I cracked it open, I landed on the Soy-Braised Goods page, featuring tofu very much like the one that’s stayed with me in my memory.

A-Gong’s Table

Traditional Taiwanese food defined the relationship George had with his A-Gong, which played out around the large round table in the wooden house his grandfather built. After A-Gong’s passing, the table went quiet, and, in the Buddhist tradition, family members abstained from eating meat for forty-nine days. During that time, the family dined at the monastery, guided by nuns in their spiritual and culinary pursuits:

...the only roof over the back kitchen is a corrugated iron sheet. The nuns cooked for us there, all forty-nine days. I remember the first vegetarian bento box they made. I remember its warmth in my cold palm when I rolled off the rubber band. In the largest section of the box, a heap each of fried tofu skin rolls and lion’s mane mushrooms squished together on a bed of steamed rice. The smaller dividers were filled with stir-fried greens, steamed kabocha, and roasted nuts. I balanced a mushroom floret between my chopsticks and took a small bite. Juices weeped from it.

(The connection between juices weeping from the mushroom and the mourning of the family members is so delicate here, so understated. George is a beautiful storyteller.)

Though he reintroduced meat into his diet after this period ended, George returned to veganism a few years later, a journey seeded by those forty-nine days. As he tells it in his introduction, when he moved back to Taiwan to write a vegan cookbook, he returned to the monastery that nurtured his family, turning to Buddhist food traditions in Taiwan.

The book that follows is written in this spirit. It is matter-of-fact, but has a searching quality and a wistful nature. It has a feeling of seeing old things with new eyes—sensing the passage of time, but also the permanence of being and doing. George is quick to point out that while he shares much of what’s he’s learned from Buddhist cooking traditions, the book itself is not Buddhist. It includes alliums (which Buddhist vegetarians do not eat) and also references other culinary practices in Taiwan that have influenced his upbringing.

What’s Inside the Book

A-Gong’s Table is straightforward and easy to follow, beginning with a description of the Taiwanese larder (where Yun Hai gets a mention, thank you, George). Instructions to make preserved vegetables and vegetarian meats are prominent, including a two-page spread on how to properly prepare dried lion’s mane mushrooms in larger batches for use in recipes like curry rice and Taiwanese “beef” noodle soup. Next, George moves through breakfast, little eats (or snacks), vegetables, soups, mains, and ends with festival food. All the dishes in George’s book are presented as part of a figurative spread on A-Gong’s round table.

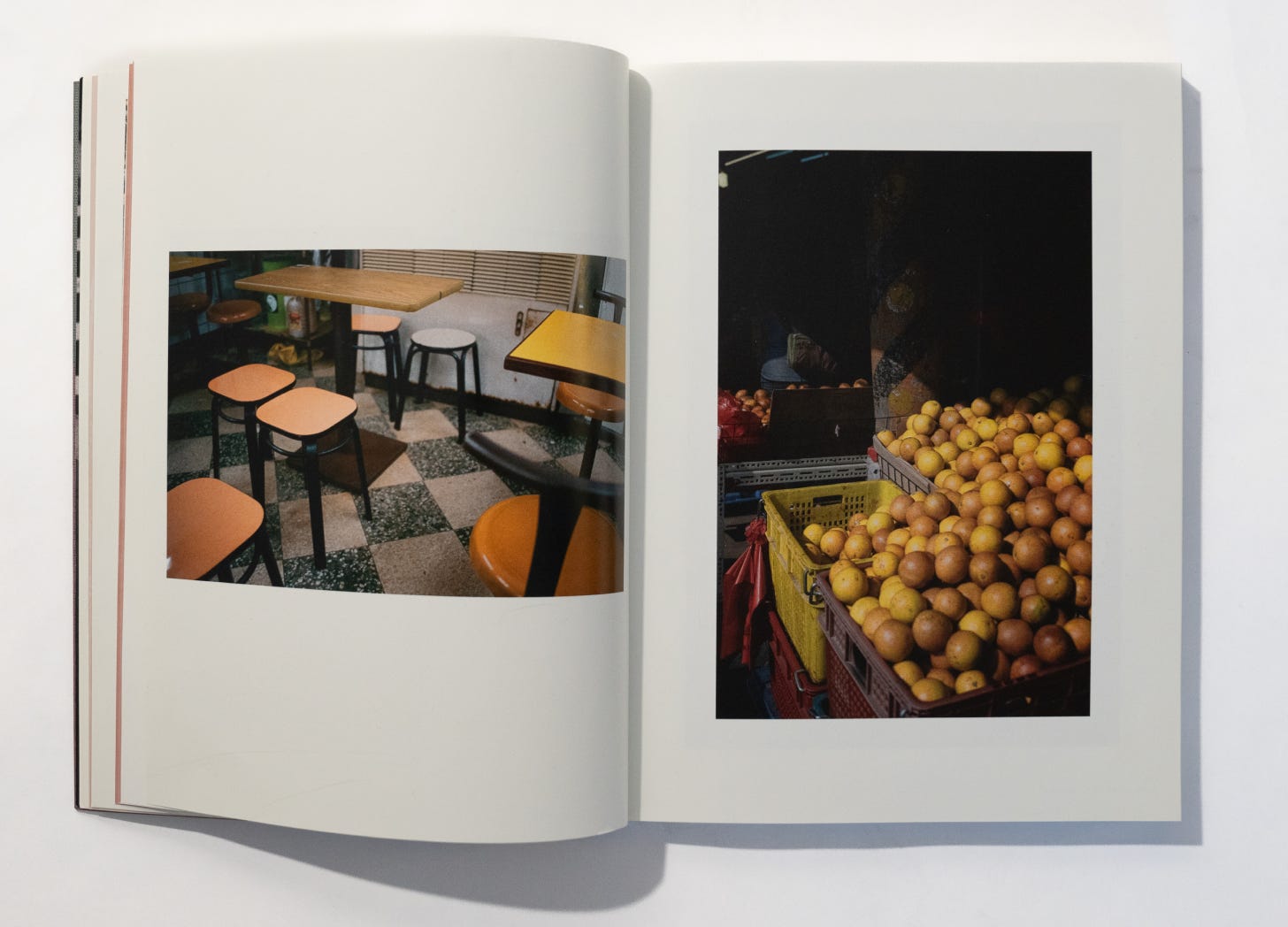

As I started reading, I found the George’s personal history and sentimentality woven throughout. It’s dotted with photographs by his friend and collaborator Laurent Hsia, who wandered Taiwan with him while developing this cookbook. Many of these images are of street scenes in everyday Taiwan, beautiful in their ordinariness. The images of the dishes were all shot at a traditional courtyard house lent by Siang kháu Lū for the shoot, giving the feel of an old residence. A-Gong is everywhere.

The design goes against the grain of the full-bleed, hardback photo books that have become synonymous with bestselling American food writing. With a paperback cover, it has more in common with cooking manuals I’ve come across in Taiwan: text and photo have equal prominence, and the more deeply you read, the more it offers. The recipe headnotes in George’s book are particularly special, layered with memory, instruction, and observation.

From the headnote for soy milk:

Watching the nuns make soy milk is a quick way to understand what Buddhists mean when they say cooking is ascetic training. Great dòujiāng is velvety smooth, nutty, and naturally sweet—a transcending experience. Their handmade process requires a trained eye and is both precise and fluid. “It’s all about experience,” says Huìqiáo Shifu, the nun in charge of operations. After a decade of tofu making, she still logs the results and parameters of each take. She dips her pinkie into the dòujiāng, gets a quick taste, and knows what proportions and temperatures she needs to adjust for the day’s batch. She then goes on to turn the elixir into perfect squares of dòubān (tofu skin), dòufǔ (tofu), and dòugān (bean curd).

No wonder the braised dougan at the Xiangde Monastery was so superb.

Rice Canteen

I met George and Laurent last month at 泔米食堂, a vegan-friendly “rice canteen” in Taipei. I was 45 minutes late because I had put the address to an ai yu and grass jelly shop into my phone instead, shocked that such a shop might also have a farm-to-table vegan menu. When I finally arrived, after a long reroute, my friends were gracious and understanding—we were all ravenous and ordered the set menu.

The small restaurant, tucked away in an alley, features seasonal food—sourced by the owner and her family—with a focus on traditional rice-based cuisine. The set menu included a main dish, a bowl of piping hot rice, a simple soup, a cube of fermented tofu, and a few small dishes of blanched and dressed vegetables. As an aperitif, we were served sweet rice water; for dessert, douhua (tofu) pudding. This simple, homestyle food embodies that clear and light 清淡 way of eating that I miss so much, absent even from my favorite Taiwanese restaurants in the states, but represented so well throughout A-Gong’s Table.

As we dined, I noticed the comments George and Laurent were making about the food in Mandarin, between bites. Observing the quality of the fermented tofu and wondering if it was from a specific maker they knew. Commenting on the fragrance and texture of the rice, all farmed in Taiwan. And noting that the tofu pudding must have been made with salt bittern as a coagulant, based on the texture. To me, this interstitial chatter was evidence of expertise and familiarity with the ingredients and processes behind the food.

George left me with an earthenware jar of fermented tofu, sourced from a producer on Daxi Street, an old port neighborhood in Taoyuan famous for its soy-based foods, featured in his text. (I haven’t cracked open the jar yet, but when I do, I’ll be sure to share a photo and tasting notes in our Notes.) Daxi is located on the Tamsui River, connected by water to Dadaocheng, Taipei’s oldest neighborhood, and Tamsui, George’s childhood home. This awareness of place as foundational to ingredient is another testimony to the respect and love George has for his home.

It’s clear to me from these interactions that George is a serious cook. Fittingly, the book can be uncompromising in its ingredient list: two types of rice wine—differing in their alcohol content—are listed, and two black vinegars, too. Toon leaves (impossible to find, but I’m ordering tree saplings) and pickled plum cordia are also called for. This is the hallmark of a truly Taiwanese perspective, but as a cook in America, it may send you on a quest. I live for this, but you if you find yourself making substitutions, that’s ok.

Still, most of what George shares is quite simple, and easy to follow. On vegetables:

It isn’t a surprise that the finest Taiwanese restaurants feature their vegetables using the same simple techniques a home cook uses. The key to delicious stir-fried vegetables is using just a few seasonings and quick techniques to retain their vitality, nutrients, and original tastes. In our home, we generally don’t use anything other than aromatics (typically sliced or minced garlic and ginger), salt, and pepper. At most, we’ll add a very small drizzle of rice cooking wine or black vinegar near the end of stir-frying. For grassier or inherently bitter vegetables like a-cài (Taiwanese lettuce) and bōcài (Taiwanese spinach), we’ll use a larger proportion of aromatics and occasionally throw in a few red chillies (minced or sliced on the bias) at the start to kiss all the vegetables with spice, or last for garnish.

Now Available at Yun Hai

We’re so proud to be launching this book with George Lee, Laurent Hsia, and Ten Speed Press. As I mentioned, George isn’t able to attend book events until later this year, so we’ve worked with him and Ten Speed Press to offer a limited quantity of signed copies. Additionally, we’ve put together a pantry bundle featuring two ingredients mentioned throughout George’s book: Wu Yin Taiwanese Black Vinegar and Organic Dried Lion’s Mane Mushroom (grown in Taiwan).

Ten Speed Press has also generously allowed us to excerpt three recipes from the book for you, dear readers. Here they are:

Three Cup Lion’s Mane Mushrooms: Use our dried organic lion’s mane mushrooms, which are grown outdoors in the high mountains of Taiwan, in this classic preparation.

Vegetarian Mee Sua: Add a splash of Wu Yin Taiwanese black vinegar, which is fermented naturally with citrus and wheatgrass, to this starch-thickened noodle soup to give the dish its signature tang.

Black Bean Tofu: Stir-fry tofu with Yu Ding Xing’s fermented black beans—earthy and savory—and pickled cordia seeds—tart and sweet—to make a perfect pairing for rice.

And finally, don’t miss our Instagram giveaway: three chances to win an A-Gong’s Table Pantry Bundle. Click the Instagram post for details

And, as always, please check out the What’s On At Yun Hai page for a list of our upcoming events. We’ve got a jam-packed May, celebrating Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month. Join us for a green tea leicha tea pop-up, a mugwort harvest, a seedling sale, the San Francisco Taiwanese American Cultural Festival, Passport to Taiwan in NYC, and a speaking engagement at Apple Williamsburg.

慢慢走,

Lisa Cheng Smith 鄭衍莉

Recipes, excerpts, and photos courtesy of Ten Speed Press, George Lee, and Laurent Hsia. Written with editorial support by Amalissa Uytingco, Jasmine Huang, and Lillian Lin. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please share it with friends and subscribe if you haven’t already. I email once a month, sometimes more, sometimes less. For more Taiwanese food, head to yunhai.shop, follow us on instagram and twitter, or view the newsletter archives.

How wonderful to see vegan recipes from Taiwan!! Thank you! <3

Yoga practitioners may also avoid alliums as "tamasic."