This is Yun Hai Taiwan Stories, a newsletter about Taiwanese food and culture by Lisa Cheng Smith 鄭衍莉, founder of Yun Hai. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, sign up here.

This week, I have the immense pleasure of inviting you to the online premiere of our new cooking show, Cooking with Steam (don’t miss the trailer below). But first, I pay respects to my inspiration—Taiwanese cooking icon Fu Pei Mei, whose legacy shaped modern Taiwanese home cooking as we know it. Read on for some history and cultural context around the mother of all Taiwanese cooking shows.

Speaking of steam, we’re also launching handmade bamboo and cypress wood steamers, made for stacking on top of your Tatung rice cooker. They’re crafted by a family workshop in Taipei, with nearly a century of expertise. Scroll to the bottom to see how they’re made.

Please join me for the online premiere of Cooking With Steam next Wednesday, December 11th at 6pm PST/9pm EST. Just RSVP below to receive a link to watch. It will ask for your number and email address; we’ll only use those to share info about the premiere.

Yun Hai is known as a Taiwanese general store, an online shop, a packaged foods brand, an importer, a food distributor, a newsletter, and one day soon, maybe even a cooking show. We’re all those things and more (much to the confusion of our business advisors ha ha ha ha ha sorry) but behind it all is the drive to teach people how to cook Taiwanese food at home.

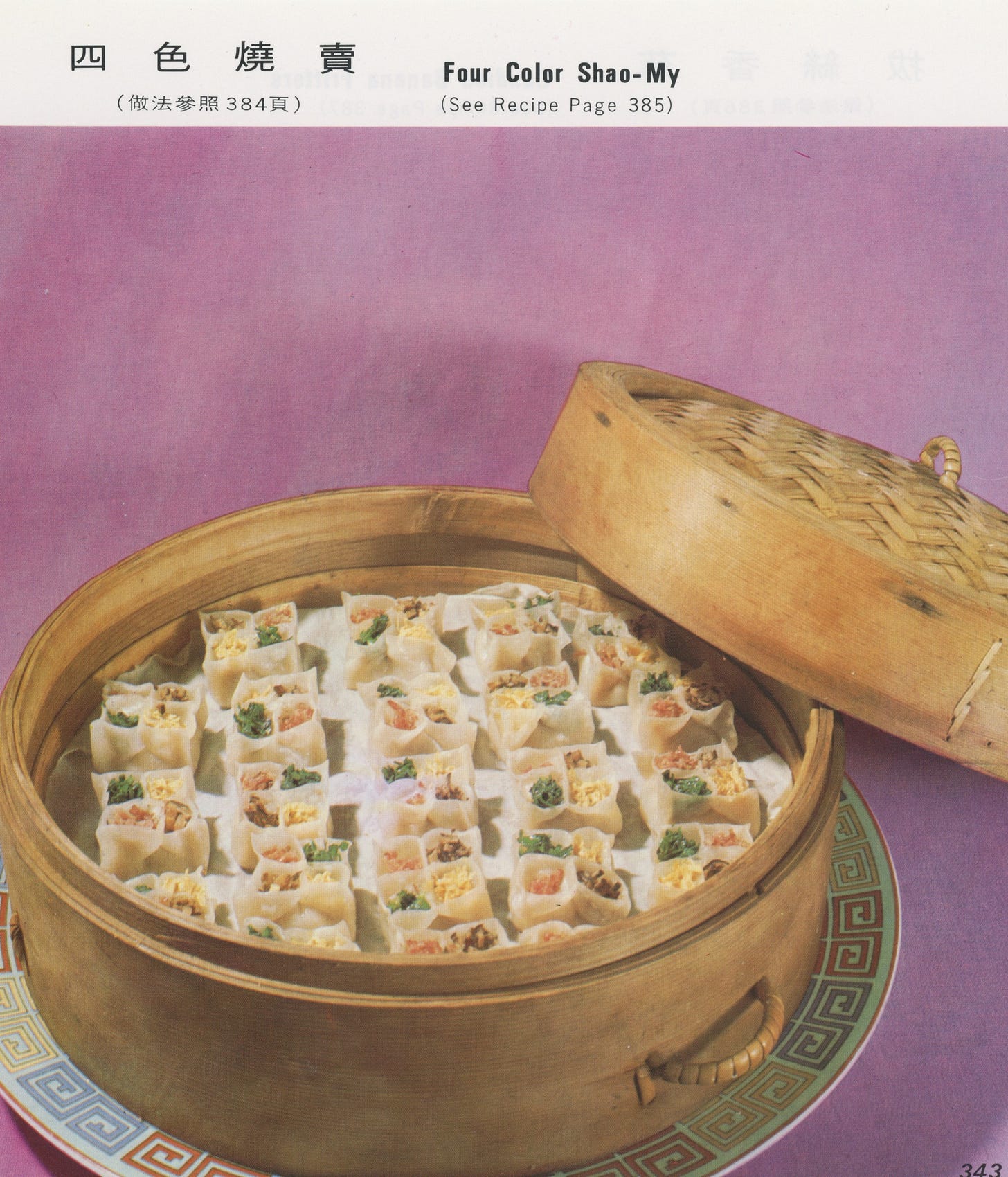

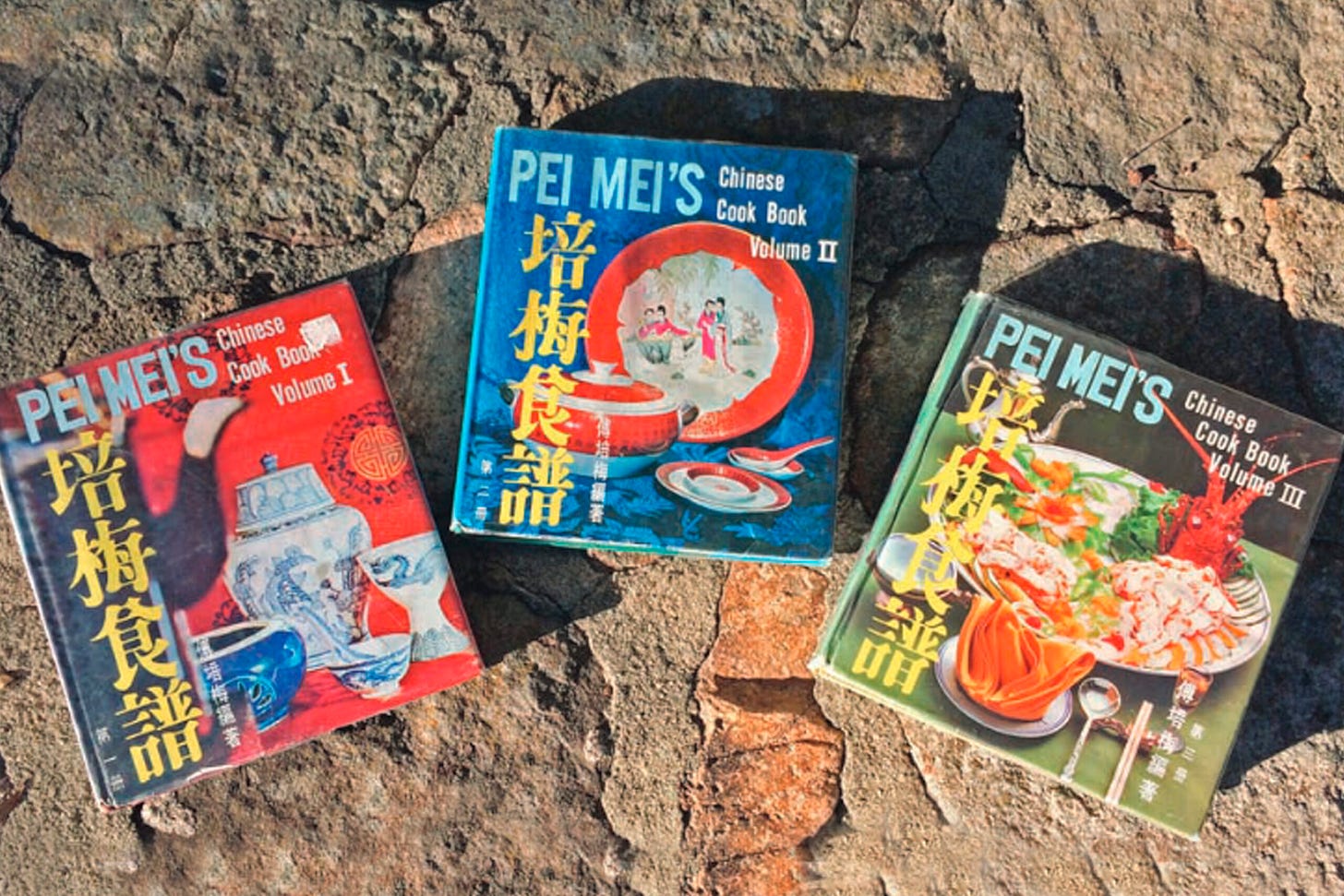

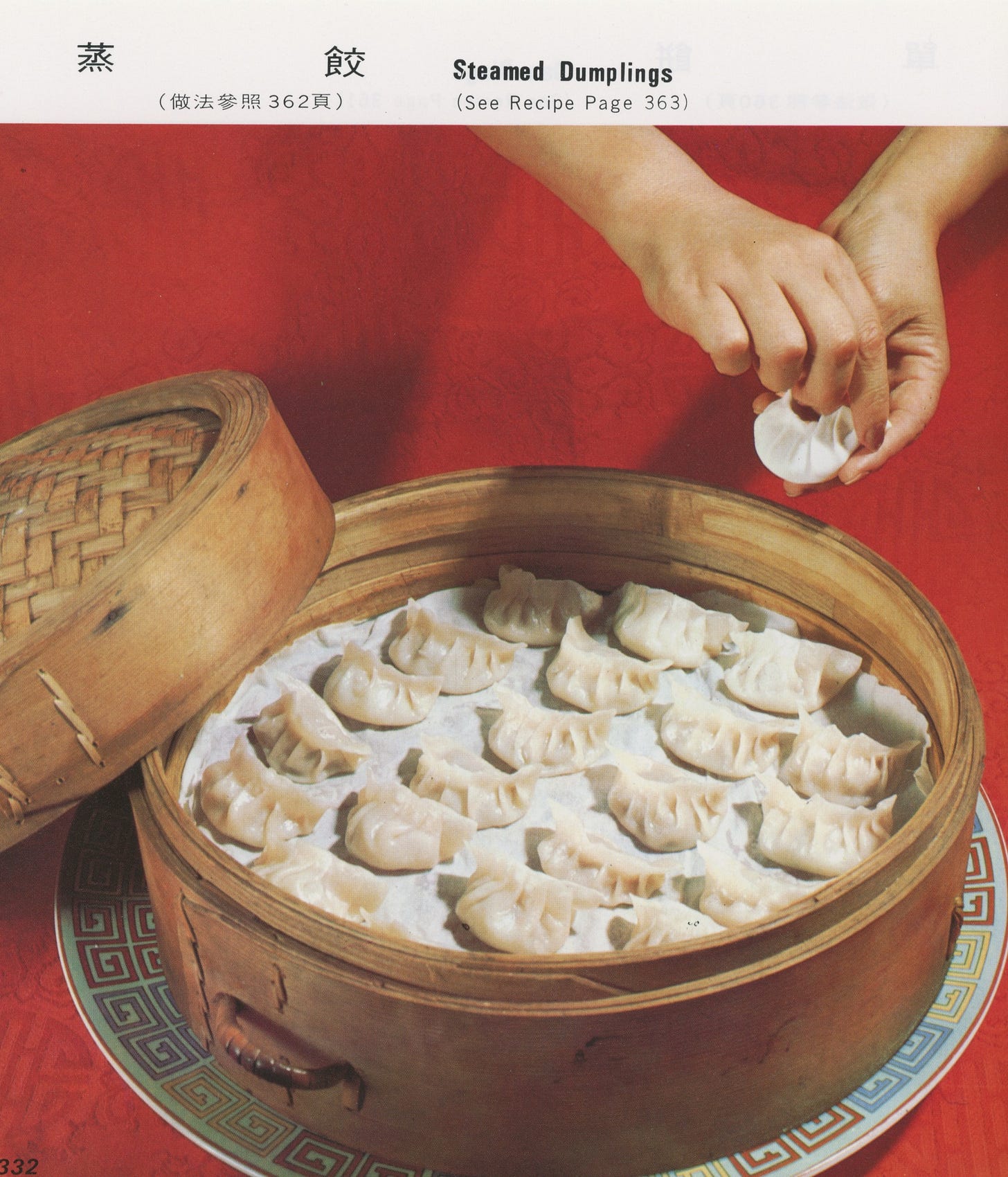

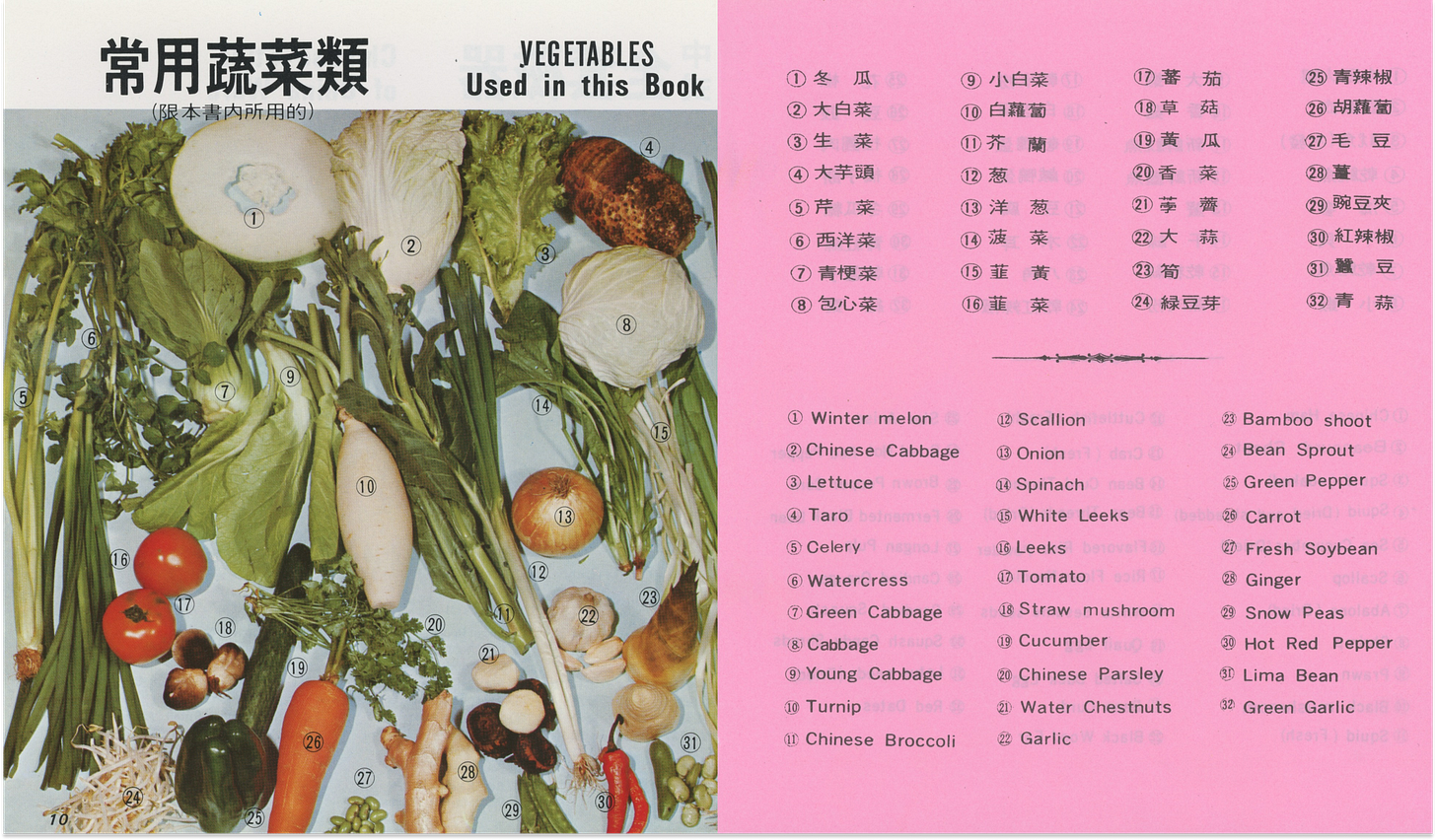

The first cookbook we sold at Yun Hai was Pei Mei’s Chinese Cook Book Volume 1, from a cache of deadstock provided by our friends at Radical Family Farms. This cookbook was one of my earliest references for Taiwanese culinary diplomacy, presenting recipes in both English and Chinese.

Many remember it from their parents’ kitchens, well worn from use, with colorful vintage photographs of dishes like Sweet and Sour Squirrel Fish 松鼠桂魚 and Fire-Exploded Kidney Flowers 火爆腰花. The deadstock books sold out in hours, but we have one archival copy of the book as an artifact in the store, given to us by Pei Mei’s son (!). It’s not for sale, but stop by anytime to browse through it.

The Yun Hai concept came full circle for me when a customer reached out and said they were happy to finally have located a Taiwanese-style vat bottom soy sauce—a rich, salty brew from the bottom of the fermentation vat, where all the umami particles settle. They had been advised by the author of the cookbook, Fu Pei Mei, in one of her legendary cooking classes, to use vat bottom soy sauce in a braise, and had been searching for it since. When I decided to import this style from Taiwan, I had not yet seen a proper version in the US, and was thrilled it helped bring Fu Pei Mei’s teachings to life.

傅培梅 Fu Pei Mei

Fu Pei Mei is frequently introduced in the West as the Julia Child of Chinese cooking. If you’ve never heard of Julia Child, so help you God. Just kidding, she’s the Fu Pei Mei of French food.

The parallels are striking: Pei Mei debuted on Taiwan television in 1962, one year before Julia, and they passed away the same year, 2004. While Julia went against the grain of the typical American housewife’s preference for convenient, processed foods, Fu Pei Mei embodied the ideal domestic caregiver, preparing traditional dishes with exacting precision. Both hosts valued cooking from scratch with careful attention to ingredients, technique, and one’s own senses.

International audiences may know her for her Chinese cookbooks, but in Taiwan, Fu Pei Mei became a symbol of post-war Taiwanese food. She made her television debut at 19, and stayed there for over 40 years, starting from a set that was nothing more than a pair of pedestals and a paper graphic of a fish stapled to the wall. When she first started teaching cooking classes in person, she did it outside, in a wok over a coal chimney which I think might also be pictured on the counter above. Many episodes of her show are posted to YouTube by Taiwan’s TTV; watch all 749 of them here. Here’s Hunanese Bacon in less than 5 minutes.

It’s important to note that she taught regional Chinese cuisines to the Taiwanese public. This focus reflected Taiwan’s fractured post-war population, which included many new migrants from across China. Her success was partially bolstered by the KMT government’s agenda to establish Taiwan as the preserver of Chinese culture, in contrast to what they viewed as its destruction in communist China. Pei Mei’s rise was certainly helped by her perfect Mandarin, which the regime viewed to be the only acceptable language at the time. In this sense, her cookbooks are properly titled as Chinese cookbooks.

Still, her perspective was distinctly Taiwanese—reflecting and shaping the diverse regional cuisines that converged in Taiwan during this period.

When she arrived in Taiwan after fleeing post-war China, she was a teenager, with no knowledge of the culinary arts. After marrying, she used her dowry to hire chefs from across China who had also taken refuge in Taiwan, bringing them into her own kitchen as teachers because there were no cookbooks available. In China, such a variety of cuisines and their master practitioners would not typically have been found in such close proximity. Notably, the vat bottom soy sauce she recommended to our customer is a distinctly Taiwanese style (see our mini-doc with Chen Office here), revealing that her expertise in Chinese cuisine had been informed by a knowledge of local Taiwanese ingredients.

So, yes, this is Chinese food, but it's also inseparable from the unique conditions that has shaped modern Taiwanese cuisine.

In contrast to her image of the exacting housewife, she was a globetrotting professional and a serial entrepreneur that managed to stay relevant over decades of social and economic upheaval. She self-published three volumes of cookbooks that she translated into English herself. She ran her own cooking school in Taiwan, judged cooking competitions, and hosted foreign dignitaries. My mom’s Taiwanese community group in Houston flew Fu Pei Mei to Texas to teach a cooking class to their constituents; she did the same for many other women’s groups across the United States.

For more about Fu Pei Mei, click on any of the links in this article, or check out Michelle T. King’s new book on her life: Chop Fry Watch Learn.

Cooking with Steam

Inspired by Fu Pei Mei, I’ve always dreamed of a kitchen studio, a place to film not only cooking shorts, but also a show—a longer-form serial with its own voice, set, pacing, and permanence, where I could share what I’ve learned about Taiwanese cooking through a personal lens. And, yes, I admit, I love the mic almost as much as I love the pen.

In 2020, when the whole p-word happened, my communal studio closed, and I immediately started looking for a space where I could set up a permanent kitchen set to film a Pei Mei style production. Although this never materialized—the storefront I settled in evolved into what is now our brick-and-mortar general store—my cooking show dream remained alive.

So now, it’s with great pleasure and anticipation that I invite you to the premiere of this long-awaited fantasy: Cooking With Steam.

The first (mini) season of this Taiwanese cooking show is self-funded, with help from Tatung HQ in Taiwan. Three episodes explore steam cooking as a foundational technique in Taiwanese cooking, starring the Tatung Steam Cooker. It’s meant for a general audience, and presented in a way so those without a Tatung can follow along, too. In the future, we hope to have the opportunity to highlight different areas of Taiwanese cooking. Please send sponsors.

The name, Cooking with Steam, is a play on the idiom "cooking with gas," and conveys an attitude as much as a technique. With this name, we honor one of the cornerstones of Chinese diasporic cooking—steaming—and suggest a gentle perspective, one that emphasizes a slow, tender way of being in contrast to the hot and fiery. The set features props that were generously loaned or given to us by Taiwanese and Taiwanese-American friends around the world.

You’re Invited to the Online Premiere

To mark the occassion, we’re doing something a little special.

You’re invited to join us for the YouTube premiere, which will be live streamed on Wednesday, December 11th at 6pm PST/9pm EST on YouTube.

There will be a short countdown to the airing of the first episode, which is just under 13 minutes, with an accompanying live chat. I’ll be hanging out and will stick around afterwards to answer any questions you might have and get your suggestions on topics for future episodes.

Please RSVP at the link above, and we’ll send you all the details when they’re ready. Feel free to share the link with family and friends. The event page will ask for your phone number and your email address, but we’ll only use those to share info about the premiere.

Our friends Night Shift Studios took us under their wing to direct and produce this, lending us one of their home kitchens, which we styled carte blanche, fulfilling, for a few days at least, my kitchen studio dreams. Much love, credit, and gratitude to them.

We have so many people to thank for this one, but especially the crew and our creative collaborators: Alec Sutherland, Sam Broscoe, Amalissa Uytingco, Dustin Wong, O.OO, Jil Tai, Ben Hill, Nathan Bailey, Bryan Bonilla, Kyle Garvey, Naomi Munro, Alexandra Egan, and Rebecca Alexander. More details and behind-the-scenes tidbits to come next week.

Bamboo and Cypress Steamers

On the topic of steam cooking, I’m thrilled to introduce a new line of products, featured in the upcoming Cooking With Steam episode: Bamboo and Cypress Steamers.

Hand-crafted by Fushan Steamer (富山蒸籠), a family-owned shop making traditional steamers in Taipei since 1949, these steamers are sized to fit perfectly on top of 6-cup and 11-cup Tatung Electric Steamers with room for the inner pot beneath. Every steamer is handcrafted using materials sourced entirely from Taiwan, without bleaches, adhesives, or chemicals.

For steaming foods, bamboo steamers are superior to stainless steel (in our humble opinion). These are crafted from alternating layers of bamboo and cypress wood, each chosen for their unique properties. Bamboo provides toughness and durability while remaining pliable and breathable. Cypress wood naturally expands and contracts with heat and moisture. Together, they wick water away from the steaming surfaces, preventing drips and waterlogged foods. As a bonus, they fill your kitchen with a warming, woodsy aroma that kisses the food with flavor.

Steamers come in sets of one or two, with a corresponding lid. For those who want to keep it simple, we also offer a single basket, which can be used with the lid that comes with the Tatung. Every configuration comes with a set of four reusable canvas steaming cloths, to line the baskets with. If you're just looking for the lid, we sell that, too.

If you don't have a Tatung cooker, these steamers can be used with a wok or a pot over the stovetop. If you go this route, we recommend keeping the water level in the wok higher than the bottom edge of the steamer (so that it’s submerged in water) to prevent burning it.

Like a cast iron pan, these handcrafted steamers will last for years with simple but specific care. Refer to our usage and maintenance tips.

Where They’re Made

Fushan Steamer 富山蒸籠 began in Taipei's Wanhua district when Xiao Sheng Yu 蕭生育, who arrived from Fujian at age 16, learned the art of steamer-making from his father-in-law. Together, they crafted steamers for local restaurants and merchants.

As Taiwan's dining scene flourished, demand for their handmade steamers grew. In 1949, Xiao struck out on his own, naming his shop Fushan (富山) after the phrase 富貴如山—or wealth as vast as a mountain. For over 70 years, the family has preserved these traditional methods, with Xiao passing his craft down to his children, who have since taken over the business.

Fushan Steamer is still well-loved for their high-quality steamer baskets, crafting them for everyone from home cooks to luxury hotels across Taiwan—including a two-meter-wide steamer basket for a banquet restaurant in Taoyuan.

How They’re Made

Earlier this year, our COO Lillian (who looks after our operations and product sourcing) visited Fushan to learn about steamer-making from Xiao Wen Qing 蕭文清 and Xiao Da Wei 蕭大為—the founder's son and grandson. One thing became clear: these steamers can only be handmade. Fushan uses machines only to prepare the raw materials.

The steamer begins with the outer frame, where the quality of the craft matters the most. Only those who've earned the title of master are trusted to bend these rings, which must be perfectly circular, sized accurately, and bent without splitting or splintering across the grain of the wood.

Once the outer ring is formed, the craftsman moves onto the interior. First, they cut strips of bamboo and cypress longer than the ring's circumference, then carefully bend each one into a circle, layering them alternately within the outer ring. It’s just a friction fit: the overlapping ends of each strip hold everything perfectly in place—no glue or fasteners needed.

Next comes an important detail: an aluminum edge protects the rim from countless lid lifts, extending the steamer’s lifespan. After fitting this, another round of wood and bamboo strips are layered in, then fastened with bamboo nails and rattan ties to secure the structure.

The base comes last—these are usually made in batches by apprentices before being transformed into finished bottoms. The craftsman presses each one into its circular frame, adds another ring of wood or bamboo to lock it in place, and finishes with those same traditional nails and ties.

Finally comes the lid, with a surprising detail: its center is made from paper sandwiched between layers of woven bamboo skin. The paper slows the escape of moisture and catches drips during cooking. Underneath, thin bamboo strips criss-cross to maintain the lid's dome shape.

Like any handmade basket, these are the product of an astounding amount of experience, knowledge, and labor. We hope you enjoy them as much as we do.

This Week’s Roundup

Taiwanese-American writer Hua Hsu (whose Pulitzer-winning memoir Stay True is available in our shop) wrote a thoughtful piece in The New Yorker about Giant Robot Magazine, a publication that chronicled Asian American subculture in the 90s. I grew up on it.

Things are moving fast over here at Yun Hai—we’re sold out of both 6 cup Tatungs and the 11 cups in green, plus a couple of the soy sauces online. But stop by our store, where we still have some remaining stock. As far as gifts go, there’s plenty to choose from! I’d recommend our box of Taiwanese fruit jams, bundled in historic Taiwanese newspapers, or our lo-fi Dried Fruit Gift Box. Check out our Taiwan Wei 台灣味 gift guide, telegraphing that ineffable essence of Taiwanese life.

Reminder that Saturday, December 14th is the last day to place your online orders in order to receive them by Tuesday, December 24th. Orders $75+ receive a free pack of dried fruit, while supplies last. And, as usual, orders $100+ in the contiguous US ship free.

ha ha ha ha ha sorry,

Lisa Cheng Smith 鄭衍莉

Written with research and editorial support by Amalissa Uytingco, Jasmine Huang, and Lillian Lin. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please share it with friends and subscribe if you haven’t already. I email once a month, sometimes more, sometimes less. For more Taiwanese food, head to yunhai.shop, follow us on instagram and twitter, or view the newsletter archives.

黑豆油: Everything I Know About Taiwanese Soy Sauce, Part One

A chronicle of Taiwanese soy sauce brewing traditions.

Woops! in one place, the premiere date said November 11th. It's actually December 11th, and I've since corrected it!

I am looking forward to the premiere! Also, loved the background on Fu Pei Mei. I've heard of her but didn't know much since she's very much before my generation, and my parents never used cookbooks. I learned something new!