This is Yun Hai Taiwan Stories, a newsletter about Taiwanese food and culture by Lisa Cheng Smith 鄭衍莉, founder of Yun Hai. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, sign up here.

Exciting news: we’re finally able to offer Taiwan-grown rices, partnering with friends Siang kháu Lū to bring you a box set featuring three distinctive single-origin rice varieties from across the island.

This gives me the distinct pleasure of being able to write about Taiwanese rice, a topic I’ve been exploring in earnest on trips back to Taiwan over the past few years. Rice is an everyday staple deeply embedded in Taiwanese life and has the unique power to reflect Taiwan's cultural, culinary, and social histories—and its future possibilities. Read on to learn about the language, botanical history, cultural context, and sociopolitical significance surrounding this flowering grass.

And, don’t miss Taste Taiwan, a self-published cookbook from Chelsea Tsai, founder of the CookInn Taiwanese cooking school in Taipei. If you’re new to Taiwanese food, this is a great place to start, with lots of great rice recipes, too.

In English, the word for rice (the food) and rice (the plant) are the same. It’s rice, for everything.

But in Chinese, the language is specific to the agricultural cycle. Dao 稻 refers to the living plant, growing in the field. Mi 米 is the name of the uncooked grains after processing. And fan 飯 means cooked rice, ready to eat.

I never thought much about this distinction until I was visiting the Yilan rice farm of Lai Chin-Sung, who started Ko-Tong Rice Club 穀東俱樂部, the first community-supported agriculture project in Taiwan. In conversation, I had mistakenly used the word for the grain when referring to rice farmer, as in mi nong 米農. I was corrected to dao nong 稻農, which uses the word for the living plant.

The course correction was casual—just a pronunciation clarification—but this shift in meaning altered my sensation of the farm immediately and significantly.

The language reminded me that the charge of the farmer was not the final product—grains—but the living plant itself, and everything alongside it: the thick, gray mud of the paddies; the small fish and crab that live there; the waterfowl that pick them off; and, of course, the stalks of rice, planted so diligently and neatly. But also, the landscape itself—an electric green, rippling moiré across working acres.

And then there’s the culture of it all. Big-wheeled, cantankerous transplanters pluck the smallest, most delicate seedling out of its sprouting sod to be deposited, one by one, into unstable mud, navigated with so much skill that not a single sproutlet is run over. The continued recruitment and education of young farmers, many of whom are returning to the land, is enabled by the internet age, allowing them to devote part of their year to farming while earning a supplemental living in the knowledge economy. The longevity of the hundreds of rice cultivars developed in Taiwan, suited to all of its microclimates, cuisines, and tastes, would disappear if not consistently planted or seed banked year after year by Taiwan’s community of agriculturalists. Stewardship of the land is imperative, which, if allowed to fall fallow, would inevitably be swept up by real estate developers, likely never to be returned to a productive plot.

A bowl of steamed rice may seem like the simplest of things. Like many of life's minimal treasures, it reflects so much: the trajectory of Taiwanese agriculture, past histories, and coming changes.

In 2024, I was invited to ride a transplanter with Lai Chin-Sung. The equipment is loaded up with pallets of seedlings, which are individually pricked out and planted by what I can only describe as “fingers” of the machine. A driver navigates the mud flat while someone mans the hopper. Occasionally, someone needs to hop out to fix something, which puts them into mud almost knee deep. They leave their shoes on deck. It was a bumpy ride; I was pretty sore the next day.

A Short Primer on Rice

Calrose, koshihikari, sekka, tamaki gold, jasmine, bomba, arborio, basmati, domsiah.

There are many different kinds of rice out there. Not to mention popular Taiwanese varieties, each as distinct as the varieties listed above: Tainan No. 11, Taichung Sen 17, Taitung No. 30, Tainong Indica No. 14, Taoyuan No. 3, Kaohsiung No. 139, Taikeng No. 9, Tainung No. 71, each named after the Ministry of Agriculture research station that developed it.

The way rice is labeled for retail—prioritizing the name of the variety over the subspecies (calrose is a variety of rice like mutsu is a variety of apple)—doesn’t give consumers much of a clue. Before I can get into the different types of Taiwanese rice, here’s a short primer on the grain. If you are familiar already, skip ahead.

1. There are only two major subspecies of rice.

Almost everything fits neatly into two drawers: indica and japonica, with some exception (javanica is a major type of rice that’s a technically a tropical japonica, and was one of the original rices grown in Taiwan).

Indica is a long-grain rice. Because it grows well in warm lowlands, indica rice tends to be favored by tropical regions with hot and humid climates. Basmati, Thai jasmine, and zailai rice from Taiwan fall into this category. It’s light, fluffy, aromatic, and doesn’t stick together.

Japonica is a short-grain rice (what we most often think of as sushi rice). The grains stick together and are a bit chewy. This rice grows in the cooler subtropics and temperate regions. Koshihikari, calrose, Taiwan’s penglai, and Italian arborio are all short-grain rices. (Yes, that means you can make risotto with penglai rice and put arborio in your Tatung).

2. Two different starches are responsible for mouthfeel.

All rice has a blend of two starches: amylose and amylopectin. Constituent ratios vary according to species and variety.

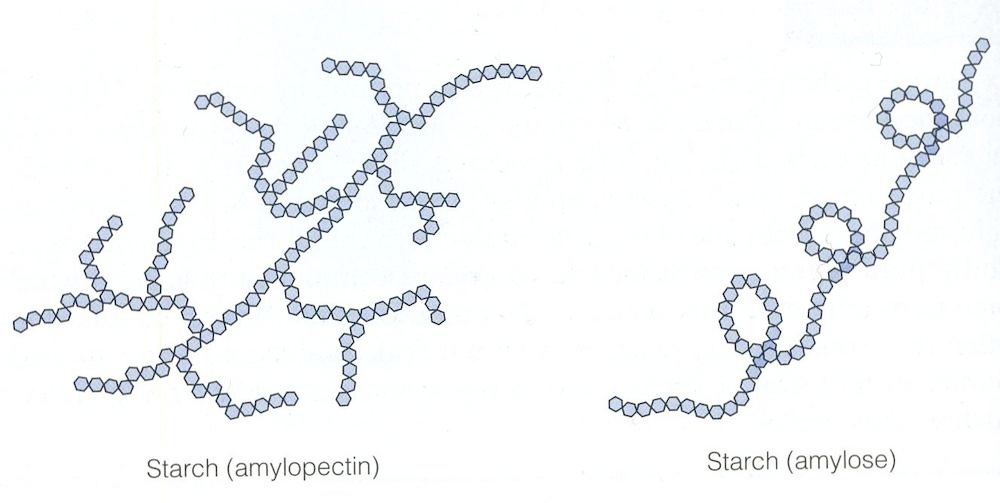

Look at their structures:

Amylopectin (left) is branched, hairy, wild, craggy. A rat’s nest. In contrast, amylose (right) is a single chain, relatively smooth. Slippery.

Rice is a kaleidoscope of texture, and it’s all to do with the interaction of these two forms. Amylopectin (rat’s nest) just wants to tangle up. Amylose slips like silk. Indica (fluffy, not sticky) is mostly amylose, and japonica (chewy, sticky, bouncy) is mostly amylopectin.

Glutinous rice is a third classification of rice that transcends subspecies and has to do with starch content. This kind of rice, which can be either indica or japonica, is almost entirely amylopectin, due to a mutation selected by farmers through cultivation long ago. This includes sweet rice (used for mochi), Thai sticky rice, and glutinous purple rice.

Taiwanese Rice Varieties

This intimate relationship between farmers and their dao extends beyond language—it's reflected in the careful study and cultivation of specific varieties suited to particular regions, climates, and culinary purposes. Taiwan produces and widely consumes both subspecies of rice, and their glutinous counterparts.

Penglai Rice 蓬萊米

Before I started researching Taiwanese rice, I thought the only rice in Taiwan was the short-grain variety, with that classic Q (al dente) texture. The association is so strong, that if long-grain rice is the only kind available, I’d almost not even eat Taiwanese food at all. That’s how important the texture is.

But, short-grain japonica rice in Taiwan is absolutely a product of the Japanese colonial era. Prior to the 1920s, people in Taiwan grew and consumed long-grain rice. Yes, slippery indica.

When Japan colonized Taiwan (1895-1945), they pursued an "agricultural Taiwan, industrial Japan" strategy. They needed to adapt Japan's preferred japonica rice—suited for cooler climates—to Taiwan's warmer environment, catering to Japanese tastes.

Japanese agricultural scientists eventually succeeded in developing a short-grain rice that could thrive in Taiwan's subtropical climate. They named it penglai rice after a mythical peak thought to symbolize Taiwan’s bounty, while dismissively labeling the existing local long-grain rice as zailai (literally "has-been"). It’s an interesting story, and beyond the scope of today’s letter, but you can read about it here.

Today, this short-grain penglai rice defines Taiwanese cuisine, distinguishing it from the long-grain varieties typical in neighboring Southern China. Taiwan remains the only subtropical region in the world where short-grain rice dominates both cultivation and consumption. Clarissa Wei explores this in her cookbook Made in Taiwan.

People often ask me what the difference is between Taiwanese food and Chinese food. I have many answers to this question, but penglai rice is certainly one of them.

Zailai Rice 在來米

Long-grain zailai rice has seemingly disappeared from dinner tables in Taiwan, but behind the scenes it’s still the foundation for many Taiwanese dishes: rice noodles 米粉, bowl cake 碗糕, and turnip cakes 蘿蔔糕 among them. To make these, zailai rice is soaked and then pulverized into a slurry, which is used as a dough-like base. The slippery, toothsome texture of the amylose in zailai rice creates the ideal consistency for steamed rice-based foods.

As a card-carrying rice evangelist, I‘m increasingly excited to use zailai long-grain rice—it connects us to a much older, pre-Japanese era culinary tradition in Taiwan.

Glutinous Rice

Ultra sticky glutinous rice is essential to Taiwanese cuisine, indispensable for making zong zi and a-bai, rice dumplings wrapped in leaves (like bamboo sticks, lotus, ginger, mao shu cai) and steamed. The adhesive quality of the rice binds these dumplings into a cohesive form that can be easily unwrapped and eaten. Glutinous rice is also used as the wrapper for fan tuan—a rice roll stuffed with meats, pickles, and eggs—or cooked into dessert soups and drinks. Beyond direct consumption, it’s made into vinegars and wines.

Here’s a sample of many kinds of rice based cuisine in Taiwan, utilizing all styles:

Taiwanese Rice Activism

Rice is so important and distinctive for Taiwan that it serves as both a measure of and a protest against the deleterious effects of globalization on the island.

According to the Washington Grain Commission, wheat consumption in Taiwan exceeded that of rice in the 2010s, even though its domestic wheat production is almost negligible. It’s sad to read this. I hate agripower.

Taiwan’s domestic wheat production is negligible at under 367,500 bushels per year. Taiwan has relied entirely on imports for its food wheat requirements for the past 50 years and will likely continue to do so in the future. Per capita, wheat consumption in Taiwan exceeded that of rice several years ago and now is stable at 119 to 128 pounds. Taiwan is a traditional rice country where wheat consumption exceeds rice consumption due to urbanized lifestyles, the sheer variety available in wheat products, and USW outreach activities funded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Market Access Program (MAP) and state wheat commissions, including the Washington Grain Commission.

This threatens Taiwan’s rice culture. As the demand for rice shrinks, it’s difficult to recruit farmers who want to carry on the torch. It reduces Taiwan’s food resiliency, as people begin to rely more on imported staple foods. And it devalues traditional culinary culture, disrupting connection to the past.

Supporting traditional rice cultivation can be seen as an act of cultural preservation and food sovereignty. There’s a group of Taiwanese folks—many of them farmers, educators, writers, chefs—that is keenly aware of this and are working to bring Taiwanese rice back into the forefront of the island’s culinary imagination. Among them is Lai Chin-Sung, whom I mentioned earlier. His establishment of Ko-Tong Rice Club and the accompanying weekly publication Rice Weekly inspired many young people to take up farming as a way of life. The developing community established an education center with a new rice farmer training camp. A local canteen serves rice-based foods made from the dao grown in town.

I owe so much to our hardworking, inspirational, compassionate friends at Siang kháu Lū, who taught me everything I know about Taiwanese rice and rice activism. Located in a traditional san he yuan 三合院 residence in Taoyuan, they promote the culinary heritage of Taiwan through kueh 粿 (rice cake) workshops, sharing the techniques and stories behind rice culinary traditions.

They also champion smallholder farms committed to traditional rice cultivation. With limited resources but endless enthusiasm, they’ve created a box set of three different Taiwanese rice varieties, each grain telling a unique story of the island's diverse terroir and agricultural heritage. We’re so proud to be their partner in the United States and introduce these exquisite single-origin Taiwanese rices alongside them.

By familiarizing a US audience with these unique Taiwanese grains, we hope to participate in the work that Lai Chin-Sung, Siang kháu Lū, and others are doing, while creating meaningful business opportunities for the small farmers that are electing to persevere and keep Taiwanese rice culture thriving.

Island of Dao: Taiwanese Rice Collection

Introducing the Island of Dao: Taiwanese Rice Collection, a set of three single-origin Taiwanese rices grown by three smallholder farmers in Taoyuan, Chiayi, and Yilan.

Siang kháu Lū, a community kitchen in Taoyuan, selected one cultivar from each of the main types of rice cultivated in Taiwan: short-grain japonica, long-grain indica, and glutinous. You can buy them together in a box set or as individual packs. Read on for more about each rice included in the collection, as well as videos produced by Siang kháu Lū featuring farmer interviews and corresponding recipes.

We’re just getting started with Taiwanese rice, and our volume, compared to most grain purveyors, is very low. If we happen to stock out, we’ll do our best to get more in as soon as possible.

I also have to acknowledge the pricing isn’t quite where we want it to be, but it’s the best we can offer while working with these initial small volumes. Our aim is to grow enough demand and refine our logistics to be able to offer a higher volume of rice at prices more suited for everyday use. In the meantime, thank you to the early supporters for giving these beautiful grains a try, and the rest for reading this story and sustaining us with your attention.

Penglai Short-Grain Rice 蓬萊米

This is the quintessential style of everyday Taiwanese rice served at home and in restaurants across Taiwan.

Bred to thrive in Taiwan's hot and humid climate, penglai rice grains are plump, moist, and Q (al dente). They absorb saucy braises, pair well with salty stir-fries, or retain shape as onigiri.

The cultivar we import is called Taoyuan No. 3, which is renowned for its light taro-like aroma, created by selectively cross-breeding penglai rice with more fragrant zailai varieties. It’s grown by farmer Chen Shih-Hsien 陳士賢 in Dayuan District, Taoyuan. I had this last night and was struck by how good it was. The scale of the grains are also noticeably different than California-grown varieties—a smidge mightier.

Recipe: Rice Pancakes

If you want to use penglai for something other than a bowl of steamed rice, try making these aromatic gluten-free Penglai Rice Pancakes for your next breakfast.

Zailai Long-Grain Rice 在來米

With a firm texture that cooks into loose, separated grains, Zailai Long-Grain Rice 在來米, of the indica subspecies, was the first staple rice cultivated at a large scale in Taiwan, different from the moister and stickier penglai rice that currently dominates the cuisine. Nowadays, it's not typically eaten on its own, but it's still essential to Taiwanese cooking.

The cultivar we import is Tainong Indica No. 14, grown by farmer Chuang Yu-Chih 莊有志 in Puzi, Chiayi. Its high amylose content and dry, robust quality allow it to be easily processed into paste and flour while maintaining its delicate aroma, making it the go-to type of rice for making rice-based foods like rice noodles, bawan (crystal meatballs), and radish cake.

Recipe: Silver Needle Rice Noodles

Try making silver needle noodles, one of my favorite Taiwanese treats. This involves extruding rice slurry through a pastry tube, quickly boiling the newly formed noodles, then stir frying them or adding them into soups.

Purple Glutinous Rice 紫糯米

Purple Long-Grain Glutinous Rice 紫糯米, alternatively referred to as purple or black sticky or sweet rice, is loved for its nutty flavor and high amylopectin content, which results in grains that stick together—stickier than short-grain japonica rice like penglai.

It can be enjoyed on its own or mixed with other grains as an everyday rice, but its stickiness makes it the rice of choice for wrapping fan tuan (rice rolls) or thickening red bean porridge.

This whole-grain glutinous rice from the indica subspecies offers both the antioxidant properties of anthocyanin (the same pigment that gives purple cabbage its hue) and the nutrient-rich makeup of brown rice. But what's special about the purple glutinous rice we import—grown by farmer Lai Chin-Sung 賴青松 in Shengou, Yilan—is that it retains a soft, chewy texture despite its whole-grain nature.

Recipe: Purple Sticky Fantuan Rice Rolls

I love fantuan for breakfast and my favorite kinds are the ones made with healthful purple rice. Get the recipe here.

Yun Hai Roundup

On Tuesday, March 11th, I’ll be speaking on a panel organized by Caroline Weaver of The Locavore, regarding local retail and small business operations. Come see us at the Shopify store in Soho at 6pm. RSVP here.

New arrival! Taste Taiwan by Chelsea Tsai is a self-published cookbook by the founder of CookInn, a Taiwanese cooking school in Taipei. She shares both homestyle Taiwanese recipes and essential ingredient knowledge, with a commitment to helping home cooks recreate Taiwanese flavors anywhere. The book weaves personal memories of her Hoklo heritage through dishes like Mom's Braised Pork Belly alongside diverse influences such as Hakka cuisine, while also celebrating Taiwan's vibrant street food culture with recipes for Gua Bao and grilled corn.

We have some dried fruit gift boxes nearing their best-before date in late April, so we’re putting them on sale at 20% off. A best-before date is not an expiration date—they will still be safe to consume (and delicious) for longer. If you’re fruit curious, this is a great time to give them all a try.

If you haven’t seen it yet, check out the second episode of Cooking With Steam, featuring Beef Noodle Soup. I might like it even better than the first one. Stay tuned for episode three, airing in about a month, where we’ll demonstrate a rice-based dish for our final show of the season.

Big-wheeled and cantankerous,

Lisa Cheng Smith 鄭衍莉

Written with editorial support by Amalissa Uytingco, Jasmine Huang, and Lillian Lin. Photos and typos by me unless otherwise credited. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please share it with friends and subscribe if you haven’t already. I email once a month, sometimes more, sometimes less. For more Taiwanese food, head to yunhai.shop, follow us on instagram and twitter, or view the newsletter archives.

大同電鍋: Taiwan and its Steam Cooker

All about the iconic Taiwanese Rice Cooker that sparked a domestic revolution.

結緣: The Baishatun Mazu Pilgrimage

Celebrating Taiwan's freedom of religion from the back of a scooter, with snacks.

Wow what a beautifully written and informative piece!! I just got back from Taiwan two days ago, from Jiaoxi, Yilan specifically ◡̈ visiting all my family (who were traditionally farmers and still cultivate crops) so this really hit home. Just captured a lot of those 稻田 you talk about with my Fujifilm here: https://www.instagram.com/p/DHd5iVxTHr4/?img_index=2

I'm so grateful to you and the whole team for shining a spotlight on Taiwanese heritage, it's so important and means so much!

Learned so much from reading this! All my life I thought 水稻 just referred to the structure of the rice paddy. Can’t wait to try some of these rice varieties!