This is Yun Hai Taiwan Stories, a newsletter about Taiwanese food and culture by Lisa Cheng Smith 鄭衍莉, founder of Yun Hai. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, sign up here.

One of the bestselling products in our brick-and-mortar is a palm-sized box of MSG, made by Taiwanese brand Ve Wong 味王. We stand by MSG and don’t subscribe to the conception of it as a harmful additive, but we weren’t sure how it would be received at the store, especially since we also source many traditional products replete with naturally-occuring umami (read: MSG).

Turns out, we can’t keep it in stock. We’re so happy to see the popularity of the seasoning, as it’s been bogged down by racist stereotypes for over 50 years. I have memories of my grandmother using this in her cooking without fear of judgement, but after realizing how much stigma came along with it, she would apologize for it. It’s a sad memory, especially given how baseless that stereotype is. Grandma was right. She always was.

Today, we launch Ve Wong online, recognizing MSG as a heritage Taiwanese food and hopefully righting some of the wrongs of our parents’ and grandparents’ times.

Read on for a celebration of MSG, an exploration of why it’s been so maligned, and a discussion of its long and fascinating history.

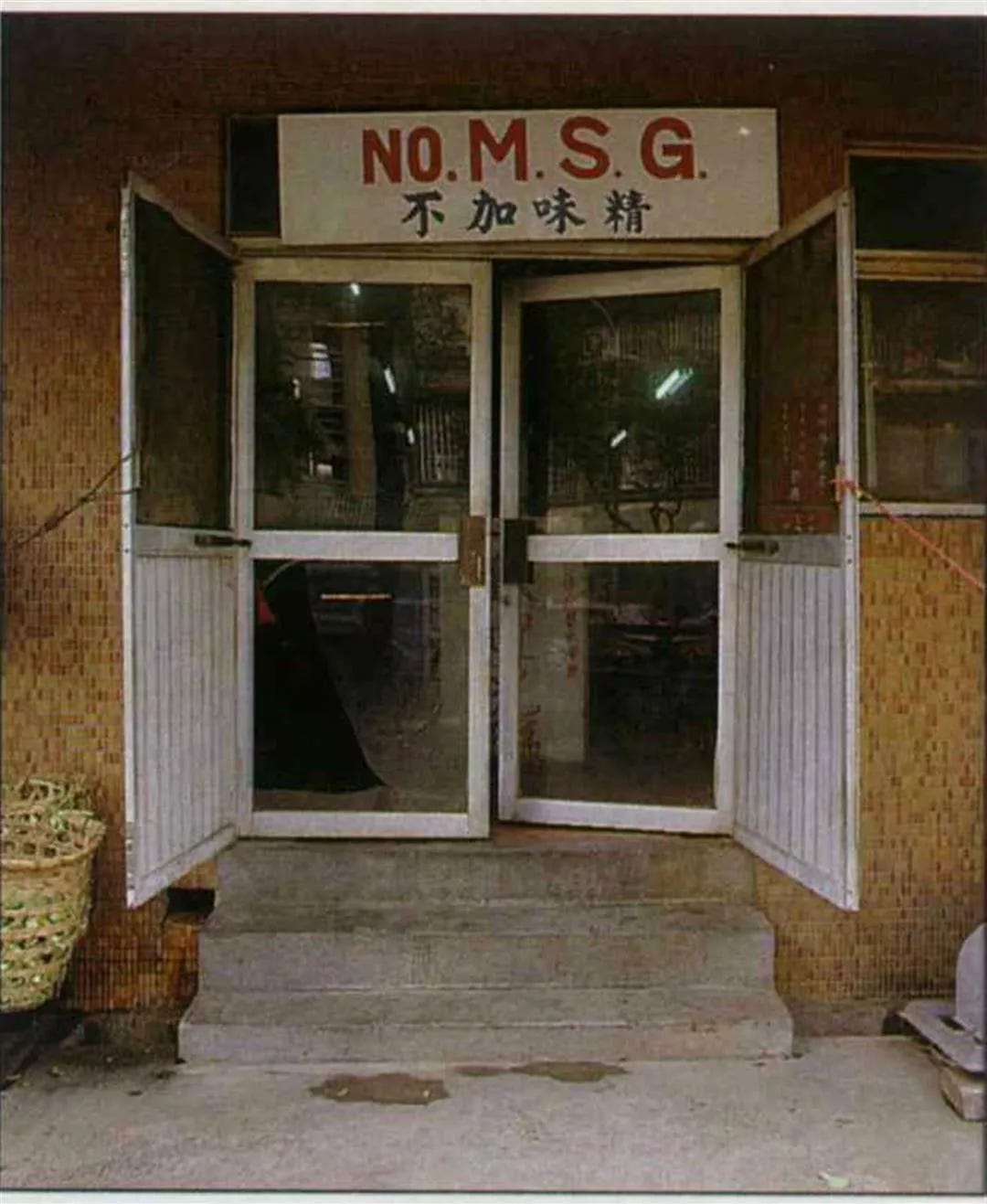

“No MSG” was a once universal sign that plagued the landscape of Chinese and Taiwanese dining in the United States—a plea to passers-by to come in and try the food, it won’t hurt you.

How preposterous and sad that an ingredient scare became such a big part of our Chinatown streetscapes. Can you imagine if Western restaurants had to do that? Posting ingredients they don’t use right next to their name? NO CHEESE?

There is a long running misunderstanding about the effects of MSG, originating with a letter to the editor published in the New England Medical Journal in 1968. The letter attributed migraine-like symptoms to MSG at Chinese restaurants, which was subsequently (and racistly) dubbed ‘Chinese Restaurant Syndrome’:

To the Editor: For several years since I have been in this country, I have experienced a strange syndrome whenever I have eaten out in a Chinese restaurant, especially one that served Northern Chinese food. The syndrome, which usually begins 15 to 20 minutes after I have eaten the first dish, lasts for about two hours, without any hangover effect. The most prominent symptoms are numbness at the back of the neck, gradually radiating to both arms and the back, general weakness and palpitation. The symptoms simulate those that I have had from hypersensitivity to acetylsalicylic acid, but are milder. I had not heard of the syndrome until I received complaints of the same symptoms from Chinese friends of mine, both medical and nonmedical people, but all well educated.

Ho Man Kwok, Robert. “Chinese-Restaurant Syndrome”. New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 278, no. 14, 4 April 1968, p. 796

This was a speculative letter, with only anecdotal evidence, and it was debunked scientifically later on. However, the stereotype stuck. The idea that Chinese food would hurt you because of rampant MSG use took off like wildfire in the United States, and worldwide. Chinese restaurants started posting ingredient exclusion signs at their doors. Instead of bringing in diners by advertising the quality of their food, they had to first respond to a racist stereotype. This spread to Taiwan, where production of MSG declined and similar signs were made.

The universality of the signage indicates the negative financial impact that MSG misunderstanding had on Chinese and Taiwanese restaurants around the world. To advertise their food by screaming from the rooftops what’s NOT in it must have been completely motivated by a customer crisis.

Growing up, I would often dine with people who felt a No MSG sign was a requirement of any acceptable Chinese restaurant. As an adult, I realized how strange this was, how much of a double standard. MSG was first discovered and produced in Japan, and has long been present in Japanese snacks and eateries in the United States and abroad. I don’t think I ever saw a No MSG sign in a Japanese restaurant growing up, in stark contrast to their presence in almost every Taiwanese-Chinese eatery we visited. Similarly, American snack producers have never been upfront about their inclusion or exclusion of MSG, and have gotten by with more acceptable names for it, like yeast extract.

I can’t say why other users of MSG weren’t compelled to renounce it the way Chinese restaurants were, but it is a sign that Chinese disaporic food seemed to be disproportionately impacted, and we’re still fighting the stigma.

The tides have turned, and we’re taking back the condiment. Now, many Chinese and Taiwanese restaurants are celebrating MSG. Bonnie’s in Brooklyn, a Cantonese-American eatery by chef Calvin Eng, serves MSG martinis. Chinese Cooking Demystified posted a hugely popular recipe for MSG noodles (making this tonight). Our friend Trigg Brown, co-owner of Taiwanese-American restaurant group Win Son, has an MSG tattoo. Chef Eric Sze, of Taiwanese restaurants 886 and Wenwen, proudly uses a seasoning mixture he dubs “Taiwan Dust”—sugar, white pepper and MSG.

We’re happy to see the embrace of this black sheep of seasonings. It’s about time we all stopped apologizing for someone else’s error.

A Brief History of MSG

Simply put, MSG is two things: glutamic acid (an amino acid that occurs naturally throughout the living world) and sodium (Na). MSG is found in tomatoes, dried shiitake mushrooms, seafood, and aged cheese, and is responsible for their savory, mouth-watering flavor.

MSG was first produced all the way back in 1908. This was the same year that the first Model T came off the production line in Detroit, which should give you a sense of how long it’s been around.

Enterprising scientist and dashi-lover Kikunae Ikeda was keen on figuring out what was making his wife Tei Ikeda's kombu stock so delicious. The discovery of MSG started there; he evaporated kelp broth to isolate glutamic acid, then mixed it with table salt, which provided the Na- ion. This mixture produced a sodium salt of glutamic acid, known as monosodium glutamate.

This also happens to be the origin story of the word umami, the Japanese name for a savory fifth taste (in addition to salty, sweet, bitter, and sour). When Ikeda isolated MSG, he realized that the compound was responsible for the savory flavor he loved in the dashi and coined the term.

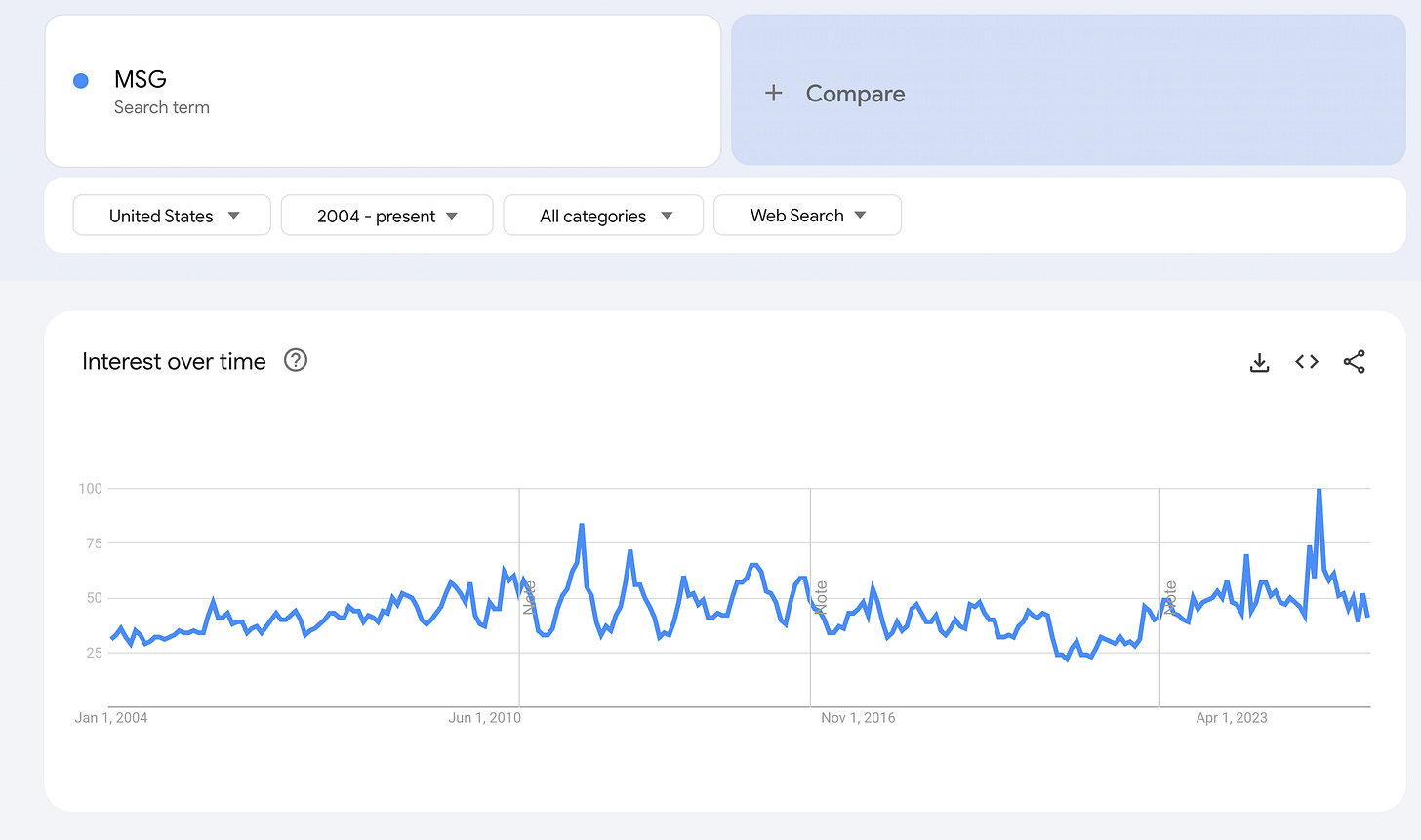

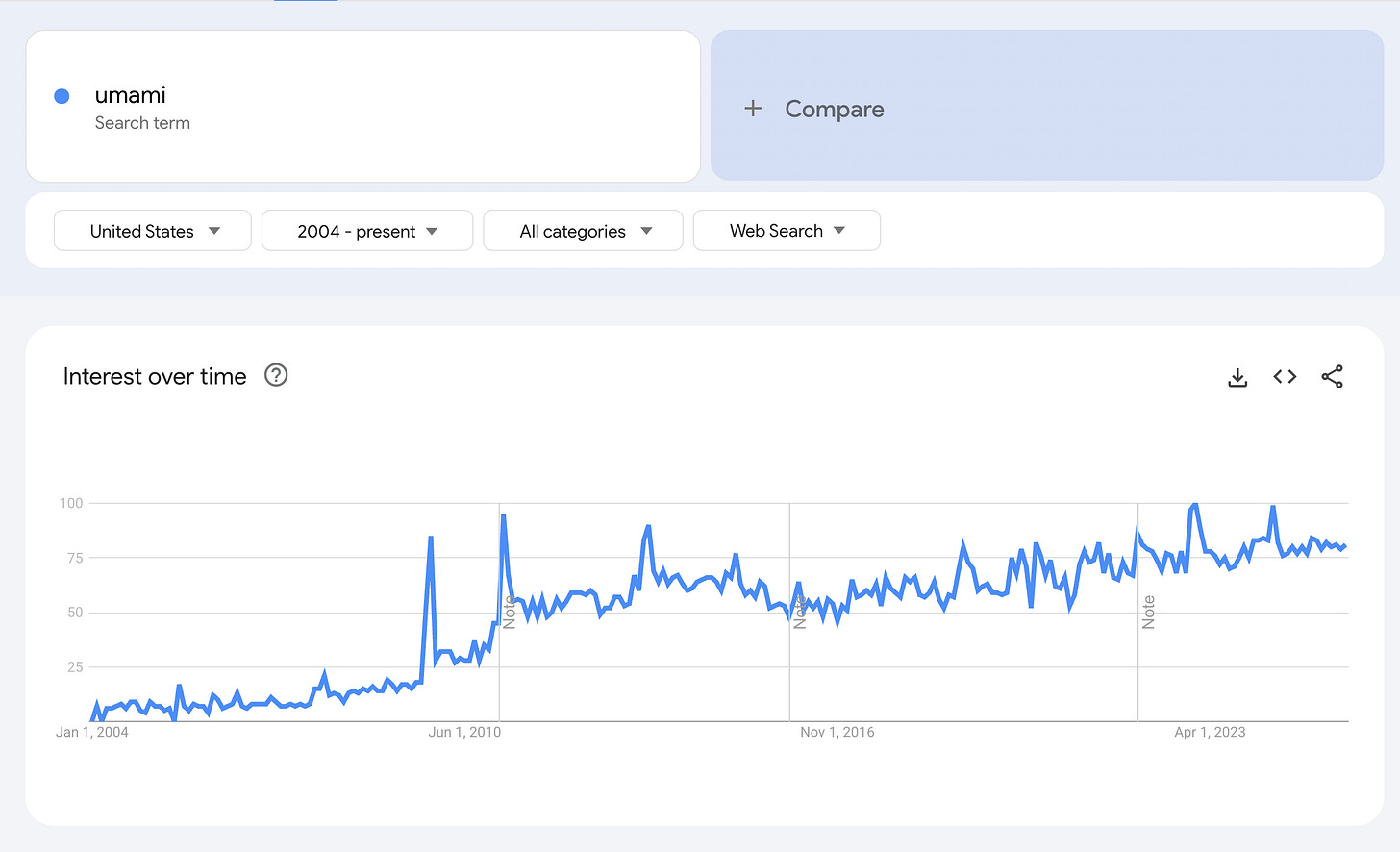

Recently, the concept of umami taken the world by storm. Despite the shared origins of the word and the MSG compound, umami has come to convey culinary desirability while MSG is still misunderstood. However, an increasing number of folks are willing to stand up for it, including us here at Yun Hai.

Ve Wong MSG

We’re card-carrying supporters of MSG and are excited to add Ve Wong, a legacy Taiwanese producer of the seasoning, to our collection. Their beautiful red box can be seen in the funeral offering in the introduction above.

I love that the box reminds me of my grandmother and Taiwanese gamadiam. The small size is perfect for how much I like to use it: just a pinch will do, here and there. I don’t need it very often, especially when cooking with ingredients that already have umami in spades, but I love it in a salad dressing (coleslaw trade secret right there) or sprinkled into a garlic and hollow vegetable (kong xin cai 空心菜) stir-fry.

Ve Wong started manufacturing MSG in Taiwan in the 60s, and became one of the major producers of this seasoning. The design of the box seems to be based on those first used by Ajinomoto, the original producer of MSG in Japan. This is indicative of the influence Japan had on Taiwan as a colony, and how much of that Japanese culinary influence is still present today. Ajinomoto no longer looks like this but Ve Wong sure does.

This cute, palm-sized box of MSG is the perfect size and format for trying this seasoning for the first time or keeping on hand for everyday cooking. It comes packed into an easy-to-use plastic bag. To store, simply keep the plastic bag inside the box and clip or tape it closed.

From stir fries to soups, all you need is a pinch to subtly punch up the savory quality of your dish. I particularly love it paired with simple foods, like lightly cooked veggies, dry noodles, and steamed egg. I wouldn’t recommend it with foods that already have strong flavoring from soy sauce or seafood, or anything with a sweeter leaning. And, like anything else, don’t use too much! You’ll overpower the original flavors instead of highlighting them.

A Note on Place of Manufacture

Taiwan was once one of the leading exporters of MSG in the world. I take that as a point of pride, especially given how historic the condiment has been in the understanding of savoriness in all kinds of foods.

Today, it’s produced by fermentation, where microorganisms convert tapioca starch, beetroot molasses, or other similar ingredients into glutamic acid. This process was actually created by Su Yuan-chih 蘇遠志, a Taiwanese food scientist.

Nowadays, Ve Wong operates MSG production facilities in Taiwan and other Southeast Asian countries. This particular pack size of MSG is produced in a Ve Wong-owned factory in Thailand.

While we exist to promote as many made-in-Taiwan products as possible, we also recognize that a number of beloved Taiwanese brands produce across multiple countries. Because our ultimate goal is to bring attention to the stories behind Taiwanese foodways, we’re choosing to include this Ve Wong product for its heritage and importance to Taiwanese cuisine. At a time when brands are being penalized by the United States trade policy for country of origin, we felt it was especially important not to exclude this legacy brand from our mix.

Ve Wong does also make MSG in Taiwan, but for larger packs only. We thought these were too large for practical domestic use, and felt the smaller ones would be better for our customers. We did ask them to make the small ones in Taiwan, to which they agreed, but only if we ordered a few thousand packs at a time.

Maybe one day we’ll hit the numbers and be able to order a massive amount of MSG from Taiwan. Until then, we’ll continue to be discerning about the origin of our products and make careful decisions about what to add and why.

A Few More MSGs Before I Go

We're working with our friends at O.OO on our own version of a lunisolar almanac, or huang li 黃曆, to be released for preorder this fall. Join the waitlist to be the first to hear when preorders open. Read about the process behind the design in our previous newsletter.

Thanks to NYTimes and the Wirecutter for including us in this great piece about best gifts for frequent travelers! We agree that our dried fruits make the best airplane snacks (and movie snacks, too, truth be told).

Tariffs for Taiwan landed at 20%. We’re told this may be lowered if TSMC agrees to invest $400 billion in the US. Stay tuned.

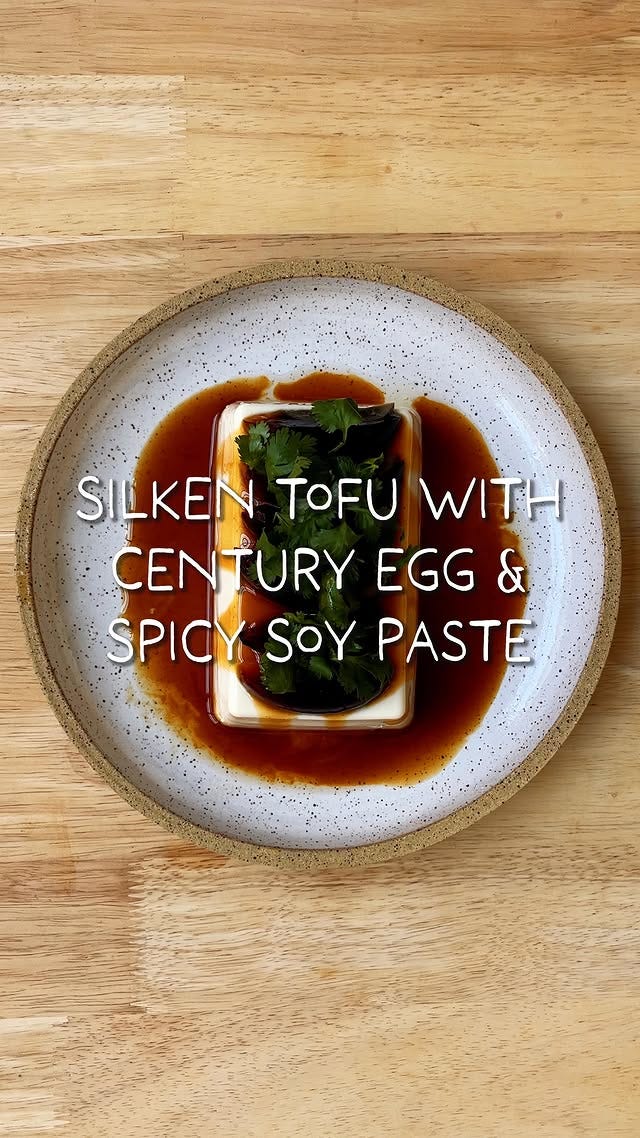

Check out this fun reel we made with Mei Liao for an easy summer appetizer featuring our spicy soy paste, silken tofu, and century egg.

In conclusion, I’ll leave you with this image of my beloved MSG keychain, procured in a small shop in Tainan a few years ago. Just another sign that MSG pride is on the rebound in Taiwan, too.

YES MSG,

Lisa Cheng Smith 鄭衍莉

Written with editorial support by Amalissa Uytingco, Jasmine Huang, and Lillian Lin. Photos and typos by me unless otherwise credited. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please share it with friends and subscribe if you haven’t already. I email once a month, sometimes more, sometimes less. For more Taiwanese food, head to yunhai.shop, follow us on instagram and twitter, or view the newsletter archives.

Studio Notes 03: Tariffs

Some context on the continued tariff saga that will most certainly drive our prices upwards soon.

米乖乖: The Little Rice Puff that Could

Another legacy brand from Taiwan that invokes the deepest nostalgia.

It’s surprising how many people still believe this. Trying to convince them otherwise is like a chicken talking to a duck. Yet they happily eat a bag of Doritos chock full of MSG without any ill effect

Love this!