Hi, it’s Lisa Cheng Smith, founder of Yun Hai. I write Taiwan Stories, a free newsletter about Taiwanese food and culture. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, sign up here.

This is Studio Notes, a paid series within that newsletter. It’s an informal exploration of the things on my desk—cultural references, first-hand research, and archival material—all in relation to how we tell stories, create spaces, and design products at Yun Hai.

Your paid subscription supports the free newsletter and our cooking show, Cooking With Steam. If you’re a paying subscriber, thank you so much! If you'd like to read behind the paywall but aren't able to subscribe, I also trade words for words—just reply to this email.

If you happen to be in New York City, don’t miss Taiwanese Waves, a free concert at Central Park featuring up and coming Taiwanese bands and performers, happening this Sunday, August 3rd.

Currently taped up on my studio wall:

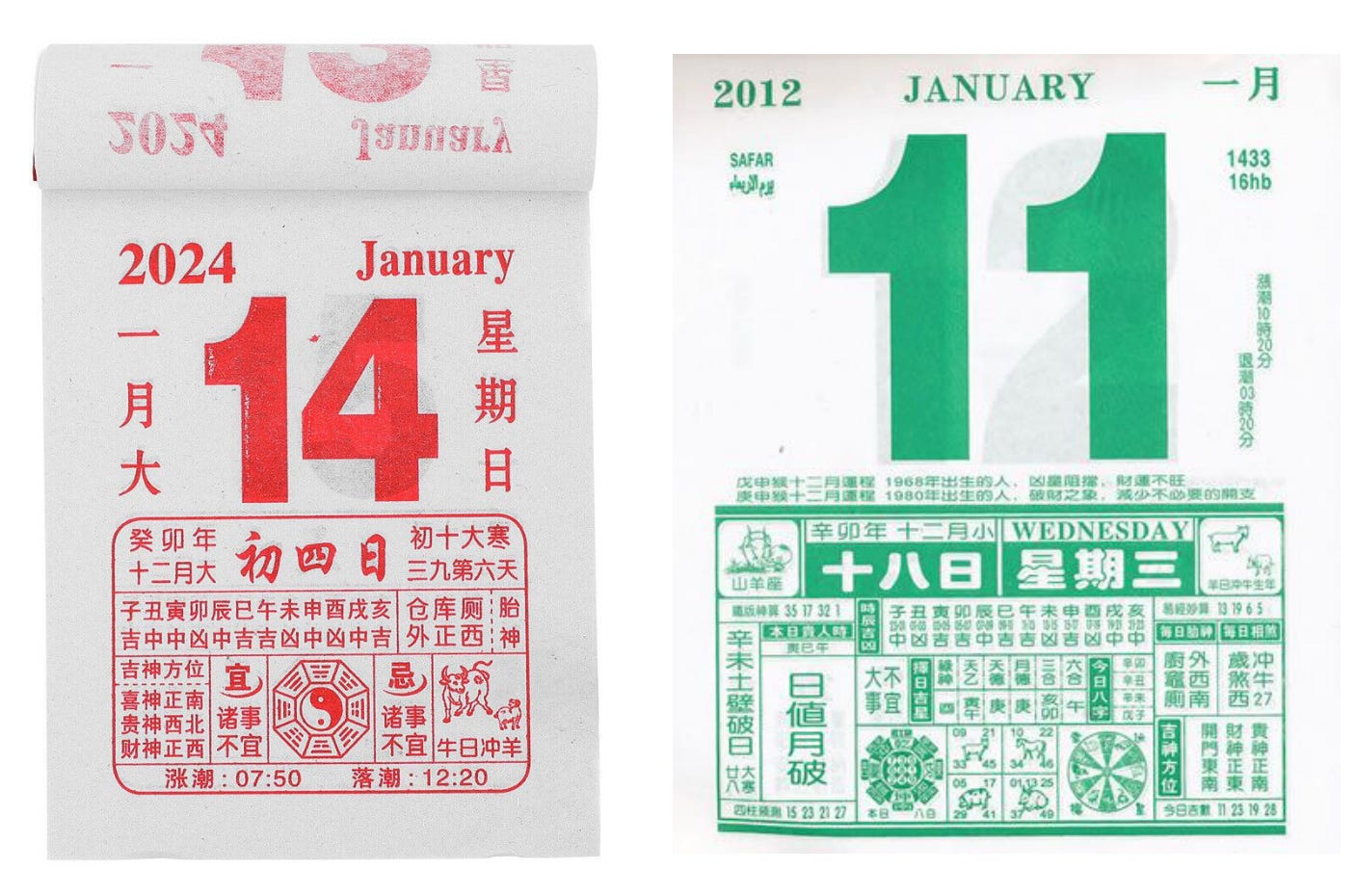

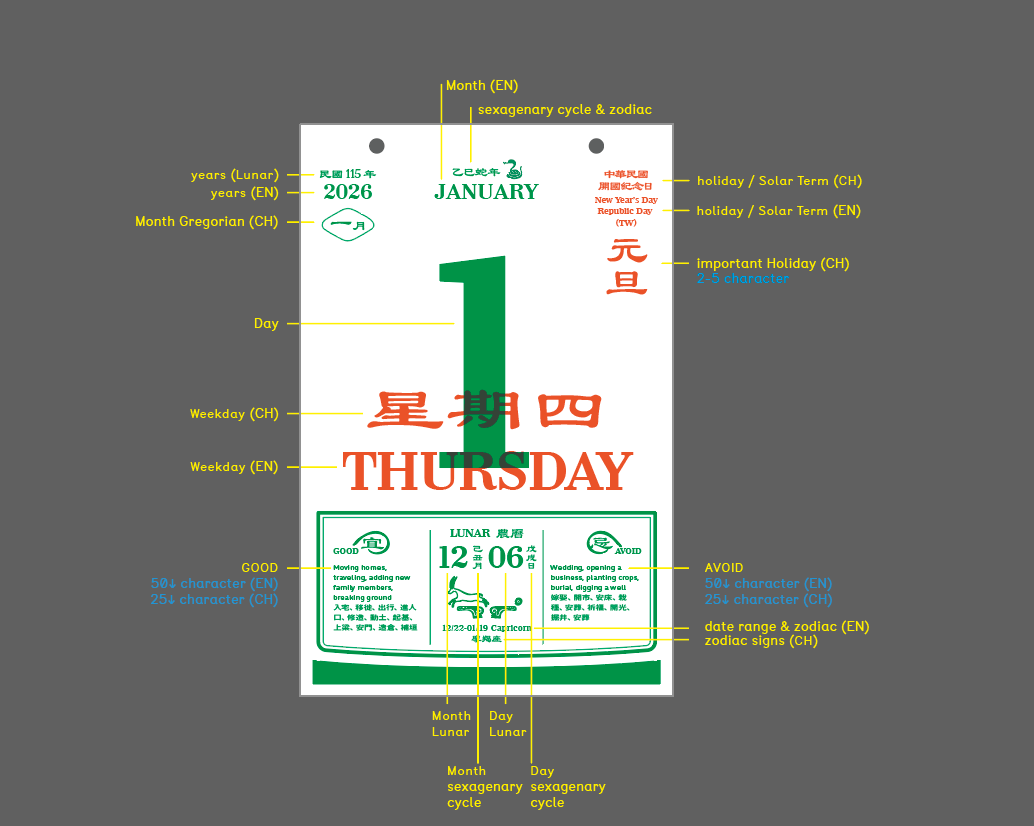

This is a page from a Taiwanese lunisolar almanac. I received it as wrapping paper in a gift from a friend. Though it came to me only recently, the page shows the weekend of September 17th and 18th. The year is there by the little Tiger mascot in the middle: 2022 or 111 年, in the Taiwanese Minguo system.

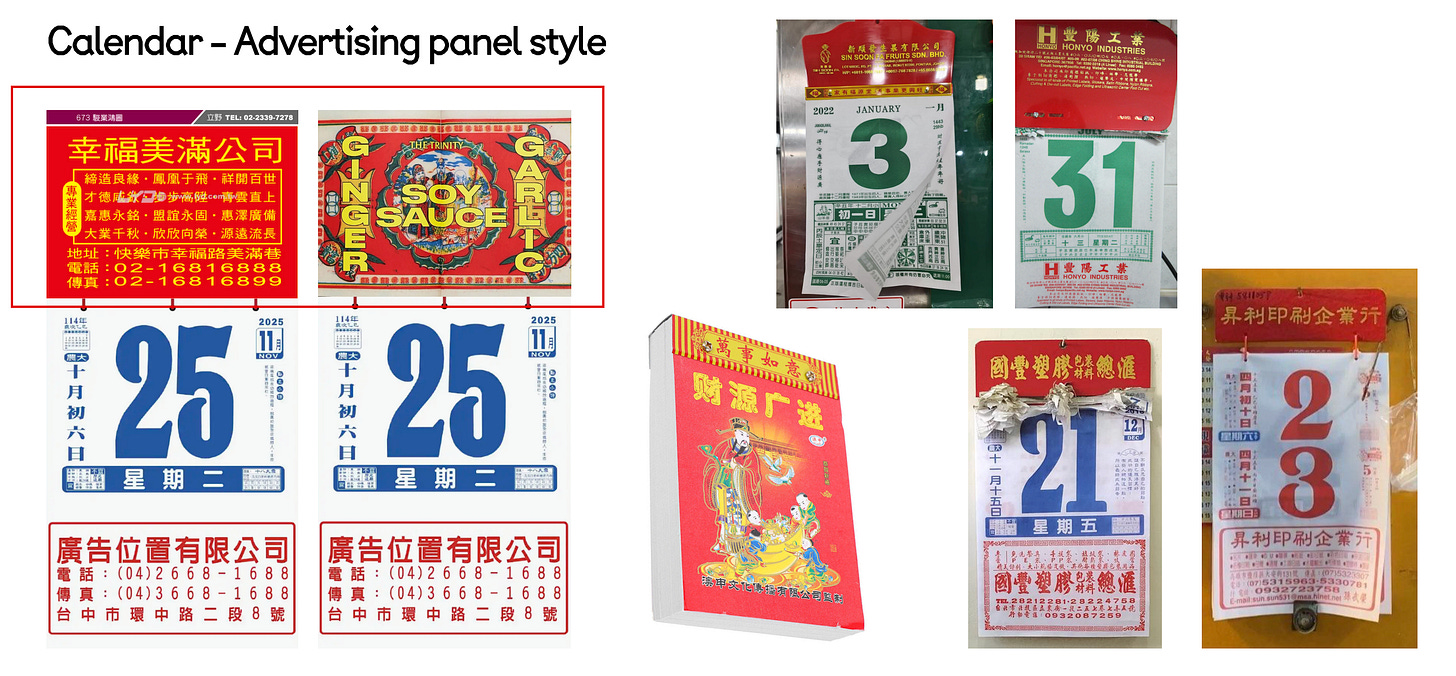

I love everything about it. The sunflower clip art, occupying most of the real estate and reminding me of non sequitur karaoke videos. The densely packed nature of the information, like a newspaper. The mish-mash of typography, calling attention to different sections while solving practical problems. The unembarrassed use of color, border, gradient, and shape. The verbose advert at the bottom, a matter-of-fact persuasion for a flour milling company.

The lunisolar almanac in the Chinese tradition is known by many names, but often as 黃曆 huáng lì, or “yellow calendar.” It’s named this because the almanac used to be the responsibility of the emperor and was identified by imperial yellow. It’s been at the top the bestseller list for over 2000 years (har har) and present in my life since childhood: hanging up on our wall, when we managed to get one; tattered and torn in our favorite shaved ice shops and Taiwanese restaurants; or fragmented into loose leaves to be reused as wrapping or scratch paper. When we receive things from vendors at Yun Hai, we still find almanac pages used to protect fragile items. I save every single one; each a monument to a day.

Beautiful and common, complicated yet plain, these pages were always indecipherable to me. There’s the date, but what’s all the other stuff?

This kind of almanac merges the Gregorian and lunar calendars, Chinese astrology, agricultural timings, and folk beliefs into a book of seasonal cycles, daily recommendations, and astrological predictions. There’s no one true form—hundreds of variations exist.

People use this information for many reasons: to mark the date, but also to determine the most auspicious times for certain activities, from crop planting to grand openings to funerals. Or, even more esoterically, to determine what direction to face when engaging in important tasks, like contract signing or worship. Much of this is still Greek to me, but more on that later.

The Yun Hai x O.OO Lunisolar Almanac

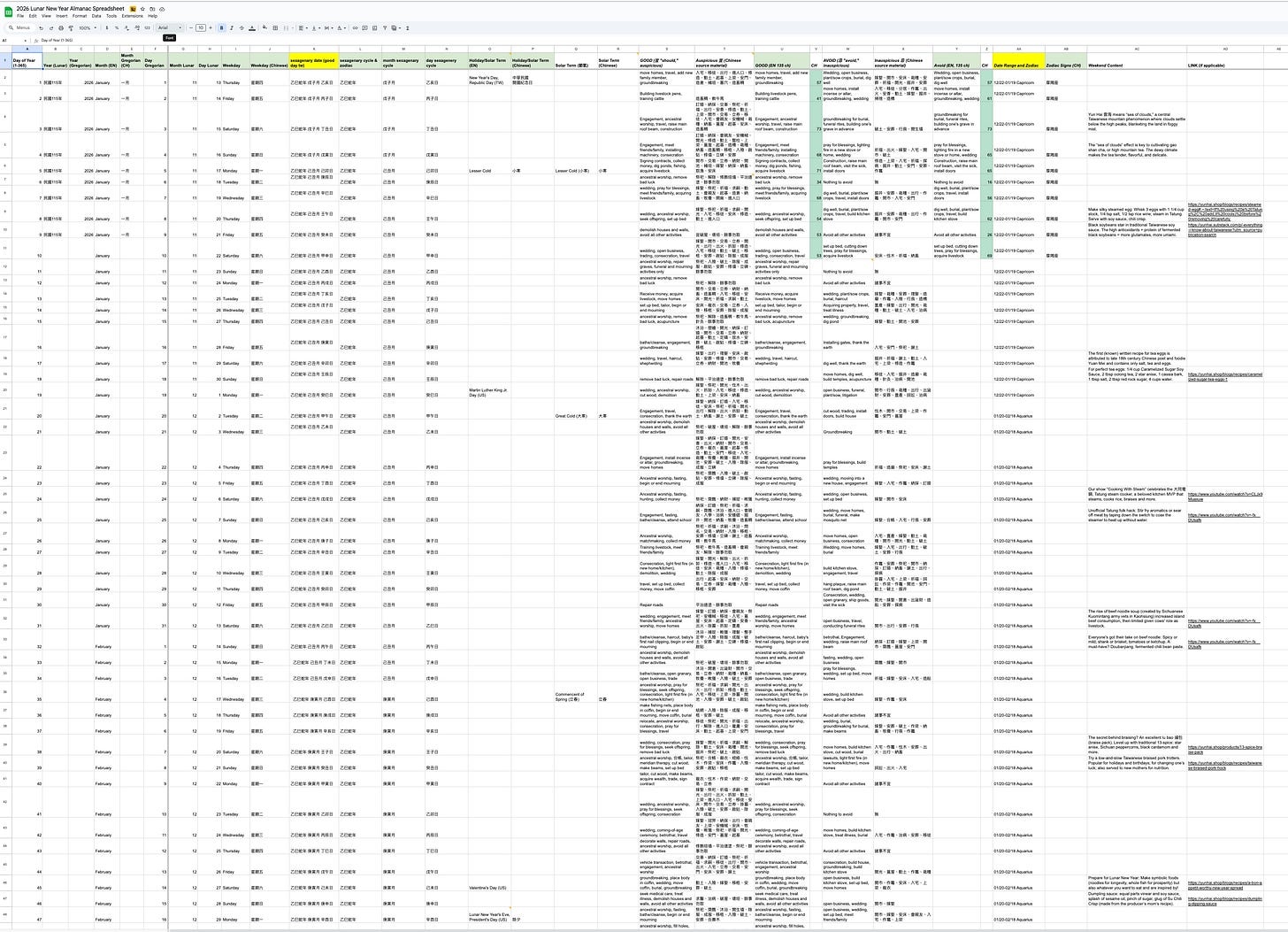

Yun Hai is in the process of designing our own 2026 lunisolar almanac, to be released for preorder this fall, in collaboration with Taiwanese design studio O.OO. Writing this in the middle of summer, 2026 feels like a long way off, but we’re in the thick of the design phase. Our project references traditional forms and verified Taiwanese sources of open source almanac data.

Sign up to be notified when it goes live.

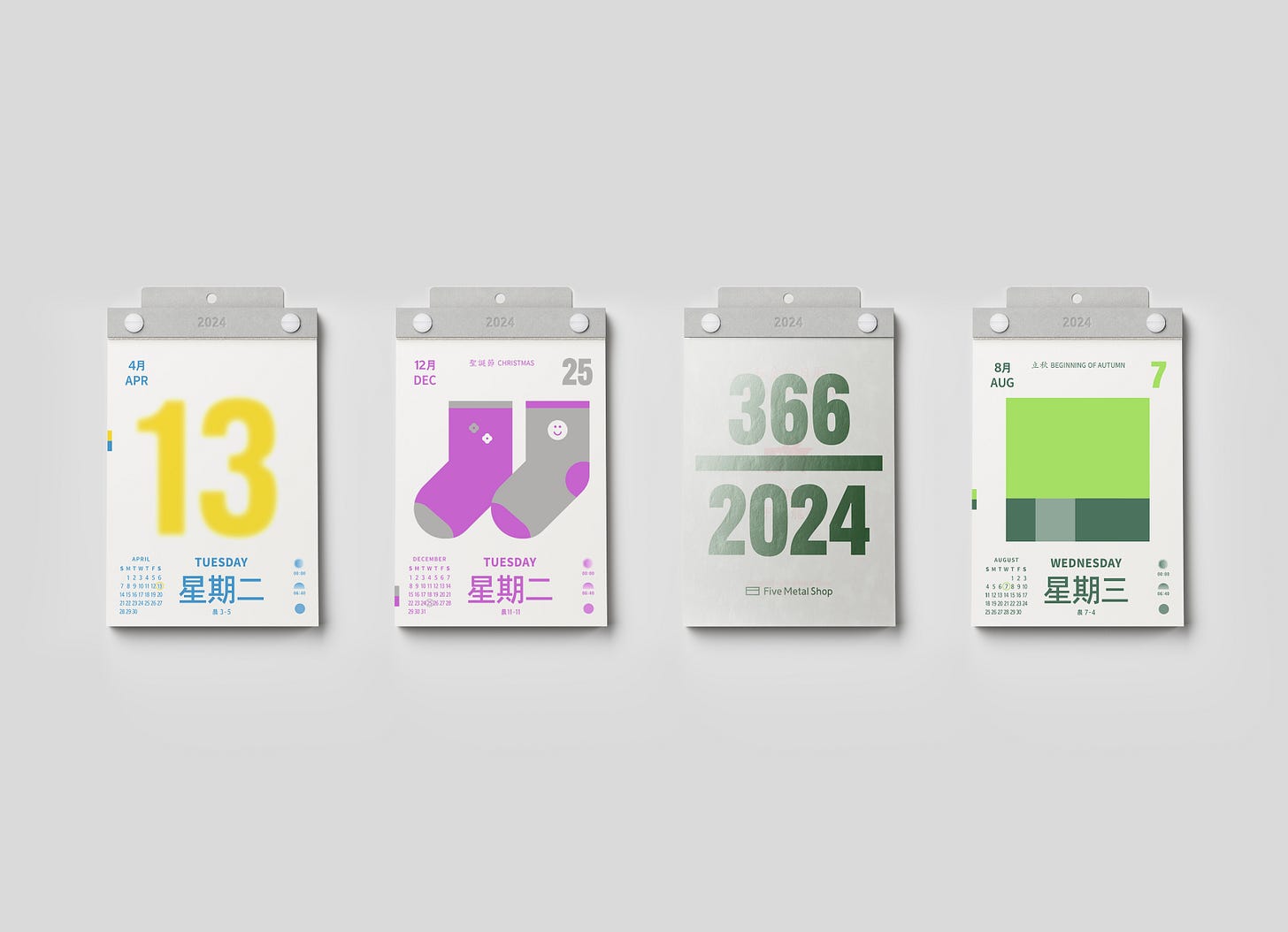

The project started as a follow-up to the now discontinued Five Metal Shop calendar, a Taiwanese almanac we distributed for a couple years (and to immense popularity) before it was halted for 2025. We’ve missed it so much that we were compelled to create our own, approaching it from a traditional and vernacular angle.

After working on the almanac this summer, I understand why Five Metal Shop eventually halted the project: it’s quite a thing to do every year. It involves managing 365 days worth of temporal and astrological data; cramming it all into a book small enough to be practical: engineering and prototyping a reliable tear-off mechanism (a factor of both backer card and paper type); and printing it all for a price affordable enough to potentially be ubiquitous. Sweat.

Happily, I got to spend a lot of time with the almanac concept, alongside designer Pip Lu and writer and activist Kimberly Chou 周存安, who wrangled most of the data. As we laid it out and examined traditional forms, I became fascinated by the origin of the information I once found to be impossibly cryptic, and it took on powerful meaning.

Our Cosmic Address

Almost all the information presented on these traditional lunisolar almanacs, from the simple date to the daily feng shui recommendations, are derived from our position in the universe. I came to think of the almanac as a sort of map, a highly technical system of calculations pushed through the black box of human culture to mark the passage of time based on our place in space.

Though I don’t subscribe to any particular astrological belief system, I do believe in seasons—cosmic, earthly, and personal. I believe in past lives, within our current selves and in the fluff we come from. I believe in the bittersweetness of the passing of time and the potential of the coming days. I don’t believe things are random, but I do believe they are mysterious. Energy doesn’t die, we’re in perpetual motion. The almanac reflects this.

The Chinese zodiac animals are based on the position of Jupiter. The Lunar holidays and calendar are based on the position of Earth’s own satellite. Our contemporary Gregorian calendar is based on our orbit around the sun, dividing that time equally according to the speed of our revolution. But, solar terms, a way of describing our seasonal progression through the year, are based on dividing the sun’s observed trip around the earth by 15 degrees. Because the earth’s orbit is elliptical, these terms vary in length and don’t fall on the same Gregorian date every year.

In other words, each day has a cosmic address, marking our relative position to the observable or calculable positions of our neighbors.

I’m a Romantic to a fault. I write that with the capital R to refer to the late-18th century cultural movement, where the wild, sublime, unknowable, and imperfect captured the human imagination over the precise, controllable, intellectualized traditions of the Enlightenment. I seek the sublime, the too-big-to-be-knowable, and I really like the things in our daily lives that capture it in their banality. The almanac tracks our cosmic position, expressed plainly on a sheet of thin paper, through human interpretive and cultural systems. It both concretizes our present reality but also abstracts it into a set of rules, like a board game. And yet, it’s full of mystery.

In this week’s paid newsletter, I thought I’d share some of what I learned about the information included on a typical lunisolar almanac, a sneak preview of what’s to come.