This is Yun Hai Taiwan Stories, a newsletter about Taiwanese food and culture by Lisa Cheng Smith 鄭衍莉, founder of Yun Hai. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, sign up here.

This week, I have the pleasure of sharing a new lineup of soy sauces from one of our longest-running collaborators, Yu Ding Xing 御鼎興, who have been producing traditional Taiwanese soy sauces since 1947. The younger generation (whatup Ozzie, whatup Byron) keeps the craft alive while introducing new varieties uniquely tuned to Taiwanese cooking, allowing me to pursue the perfect tea egg.

Today, we’re launching their new caramelized sugar soy sauce (for the soy braise lovers of this world); a spicy soy paste (quite zippy); and a sugar-free version of their single-origin finishing sauce (by popular request).

(If you’ve never encountered Taiwanese soy sauce before, check out this mini-doc we made with our friend Steve Chen on YouTube).

你們 been asking and we are here to deliver: the final production run of the Tatung miniatures is here. These babies are made on the same factory line as the real thing. This is the last time Tatung will be producing them because I think they’re tired of shutting down rice cooker production for the sake of these tiny collectibles. Run if you want. Walk probably ok, too.

Finally, I’ve been asked to kindly let you know that we may have to discontinue our free shipping policy, pending tariff impacts and shipping rate increases, so this might be a good time to buy.

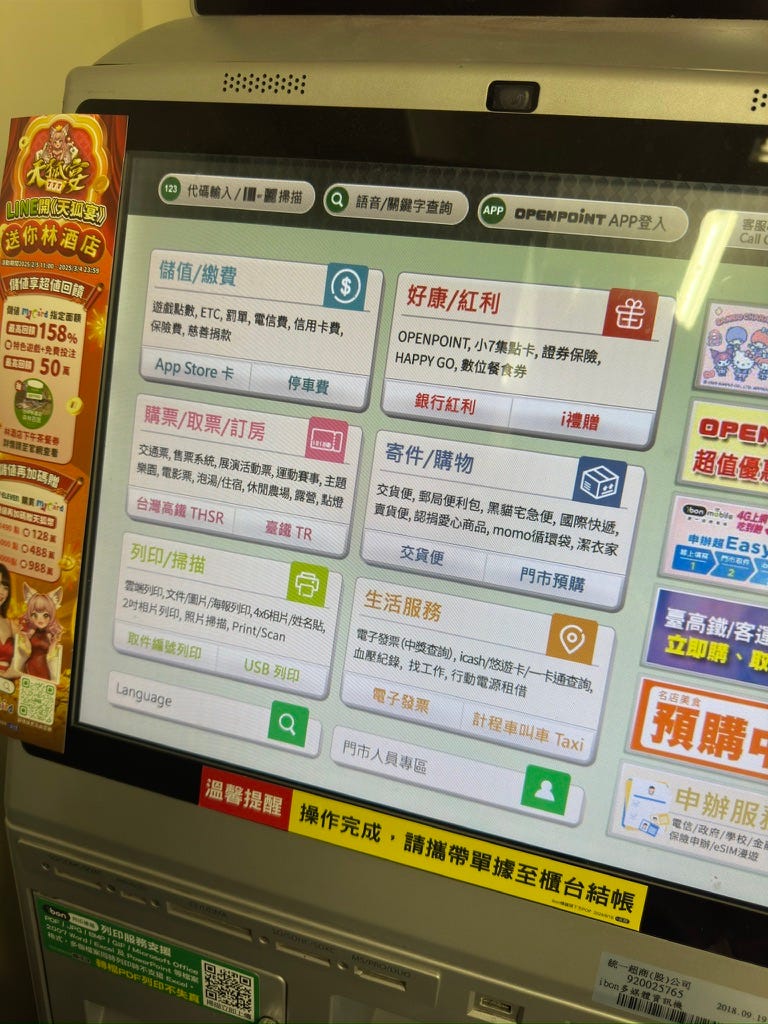

Taiwan has one of the highest convenience store counts per capita in the world—one for every 1,500 people, depending on who you ask. 7-Elevens hold the lion’s share of the market. Other than the name, they differ entirely from the American version, and have been developed into a non-negotiable piece of Taiwanese daily infrastructure by Uni-President Enterprises Corporation, who purchased the license to use the name in Taiwan.

LA Times columnist Frank Shyong reminisces:

The store looms so large in Taiwanese life that it might as well be a government agency. At any 7-Eleven, you can pay your taxes, ship or pick up packages, drop off your laundry, check your blood pressure, return library books, send faxes, buy rail and plane tickets, purchase internet access and, as a bonus, use the receipts for everything to play a lottery.

Taiwanese daily life revolves around Sevens (as they are affectionately known) and it would be only a little stretch further to say that Sevens revolve around tea eggs, which are located in big Tatung-esque vats at the heart of every store, along with Japanese-style oden, sweet potatoes, Taiwanese sausages, and steamed buns.

I’ve seen Taiwan’s annual tea egg sales pegged at 40 million, but I think it must be more. 23 million people live on the island, and I’m sure most of them eat more than 1.73913 tea eggs per year.

I love everything about them. The mingling of the astringent tea fragrance with the warmth of rock sugar and braising spices. The ceramic-like appearance of their surface, marbled and stained like the bottom of an old celadon tea cup. Their chalky, olive-colored yolks, cooked until almost powdery (it’s punk to love a dry center in the jammy yolk’d America of today). Plus, the subtle caffeination puts the slightest zip in the zither.

Color Story

As I began to explore corners of Taiwan a little further out than the local 7-11, I had some truly exquisite tea eggs in the high mountains of Alishan and Nantou (tea country). Their mosaic surfaces were criss-crossed with rich red-brown color, and even the yolks were imbued with the fragrance of the tea leaves.

In my initial efforts to recreate these eggs at home, I struggled to balance the delicate tea flavor with a rich color. The darker the color, the more appetizing the egg, but the heavier the soy sauce flavor. The more delicate the taste, the more pronounced the pallor.

As I continued to research Taiwanese and Chinese ingredients and methods, I learned that caramelized sugar was traditionally used to lend a rich red color to braises, instead of soy sauce. This technique has largely been replaced by the dark soy sauce of southern China—a milder, syrupy soy sauce with added caramel color, often artificial—but look carefully and you’ll still find caramelized sugar in kitchens throughout China and Taiwan.

In the video below (8 minute mark), a Sichuan chef makes Lu Rou Fan, but first caramelizes sugar in order to color the braise. Not exactly the traditional Taiwanese way, but an excellent demonstration of how caramel base is prepared: fry the sugar until it caramelizes, then flood it with boiling water.

I also came across the first (known) written recipe for Tea Eggs, memorialized in Recipes from the Garden of Contentment 隨園食單 in the late 18th century by Chinese scholar and poet (foodie) Yuan Mei.

Here’s the translation, posted by FatMiewChef:

茶葉蛋 雞蛋百個,用鹽一兩、粗茶葉煮兩枝線香為度。如蛋五十個,只用五錢鹽,照數加減。可作點心。

Take one hundred chicken eggs, add one liang of salt and coarse tea leaves. Boil for two incense sticks of time until done. If there are only fifty eggs, add five qian of salt, and increase or decrease the quantities of ingredients as required. They can be eaten as a snack.

Notably, the recipe contains no soy sauce (or sugar) at all. This really supports my theory that tea, not soy sauce, ought to be the dominant flavor.

(By the way, incense sticks were an ancient way of keeping time. Historians seem to think each one corresponded to two hours, as mentioned in the FatMiewChef article linked above.)

In Pursuit of the Perfect Tea Egg

When my friends Josh Ku, Trigg Brown, amd Cathy Erway asked me to contribute a recipe to the Win Son Cookbook, I combined these two points of research to develop a method to make extra-fragrant, extra-beautiful tea eggs, using caramelized sugar as the color base so I could cut down on the soy sauce. A few years later, I published an improved version in our Yun Hai Tatung cookbook that could be made easily in the Tatung Electric Steamer.

Much like the video from the Sichuanese chef above, the process starts by caramelizing sugar in a wok as the base for the brine. I came to love this caramelized sugar method. Not only does the caramel augment the tea, it creates a rich color, a glossy sheen, and a toasty flavor that could not be matched, in my opinion, by coloring with soy sauce alone.

These caramelized sugar tea eggs are always a hit. I make them for the shop for special occasions (and surely will regularly when we go deli mode). They were also requested for my mother’s 70th birthday party, where every single one of the triple batch I made was consumed by her core group of Taiwanese intellectuals (daughter win).

Caramelized Sugar Soy Sauce

I’ll be the first to admit that my recipe is simple in concept but not easy (let’s just say it’s not not arduous). More often than not, I’d add a can of Coca-Cola into the brine instead—a lazy woman’s caramel.

So, I’m very excited to announce a new addition to our soy sauce lineup: Yu Ding Xing’s Caramelized Sugar Soy Sauce, formulated specifically to bring the color to your cheeks, so to speak. The first time I heard about it, I immediately thought “no more coca-cola.”

The soy sauce is mixed with caramelized Taiwanese sugar, creating a hybrid seasoning and coloring agent. It’s Taiwan’s answer to southern China’s dark soy sauce and can be used in a similar way. Add a small amount of it into braises for richness of hue (both utilizing and shortcutting the traditional caramelization technique) while adding a toasted, buttery flavor.

If you’re someone who likes to make tea eggs, soy eggs, lu rou fan, dong po pork, scallion oil noodles, red-cooked meats, or any other richly colored food, I’d wholeheartedly recommend this to key up your chroma. But, a word of caution: do not use this as a regular soy sauce. It’s somewhat sweet, very rich, and very dark. One to two tablespoons can color two pounds of pork belly. If you need more soy sauce for flavoring (you probably will), combine it with a different, lighter type (may we suggest this one finished over a wood fire).

How It’s Made

Taiwanese soy sauce is its own unique style, made from black soybeans (instead of yellow), and traditionally does not contain wheat. This results in a richer brew than the Japanese-style soy sauces that dominate the American market. Yu Ding Xing explains that if you heat up Amber River, the smell will be “wild and crazy like a monster,” full of bold notes and rich flavors.

When we first got started, we made a beautiful mini-doc about this soy sauce brewing family with filmmaker and architect Steve Chen. It’s still one of my favorite projects (though there are many):

In true Yu Ding Xing fashion, the brewers pulled in far corners of traditional Taiwanese foods for this new soy sauce, honoring the island’s sugarcane farmers and original sugar producers, who were a key part of Taiwan’s agricultural industry during the Japanese occupation. Sugar was once a big deal in Taiwan; now there are only two remaining factories.

Their soy sauce contains two types of sugar, both produced by the 虎尾糖廠 Hu Wei Refinery owned by 台糖 Tai Sugar, Taiwan’s national sugar company, who still makes most of the sugar on the island.

The first type of sugar is san wen sugar 三溫糖, or Sugar of Three Warmths. It’s known in Japan as Sanonto Sugar, where it’s also used in simmered foods. This light brown sugar is made by cooking leftover sugarcane syrup three times, and adds a soft sweetness in the typical Taiwanese-Japanese style.

The second sugar is the Hu Wei classic 特砂 Te Sha sugar, which translates to “special grain.” Its large crystals were developed especially for long term storage in Taiwan’s humid climate. This sugar is meticulously caramelized by Yu Ding Xing to add color and aroma.

Just like my tea egg recipe, caramelizing sugar at the brewery is an arduous process. They cook 45 kg at a time, slowly stirring it over two hours, without the addition of water or any other liquid. There’s a precise point where the sugars have just broken down and browned, but not yet burned. Yu Ding Xing prides themselves on hitting this point exactly, when the sweetness of the sugar is at its lowest, and the color and aroma at its best.

Then they add both the sanonto sugar and caramel into the soy sauce during its final reduction, just before being bottled.

In the name of the soy sauce, they use the poetic phrase tang wu 糖烏, which translates literally to “sugar blackened,” indicating the importance of the color to its development. For an even more vivid visual, know that the word for black used here also means “crow.”

A New Caramelized Sugar Tea Egg Recipe

After receiving this soy sauce, I wrote a new recipe using the Caramelized Sugar Soy Sauce, a perfect shortcut for tea eggs and braises where you want a deep color and old style flavor.

Makes: 6 eggs

Prep Time: 20 minutes

Cook Time: 40 minutes, plus overnight soak

Ingredients

6 eggs

1/4 cup Caramelized Sugar Soy Sauce

2 tbsp of Red Oolong Tea

2 pieces of star anise

1 piece cassia bark or cinnamon stick

1 bay leaf

1 piece licorice root and/or sand ginger (optional)

1 tbsp Taiwanese Frost Salt

2 tbsp of red rock sugar

4 cups of water

Instructions

Gently tap the blunt end of each egg with a wooden spoon to introduce a hairline crack. This will allow air to escape during cooking, avoiding that "flat end” that appears in hardboiled eggs.

Put the eggs into a bowl on top of a Tatung steamer insert. Add a half rice cup of water to the outer pot and steam for roughly 10 minutes. If you aren’t using a Tatung steamer, boil the eggs for about 6-7 minutes, until the whites are fully set.

Rinse the eggs in cold water to cool them for handling. Then, tap them all over with the back of a wooden spoon to crack the shells. Don’t do this too hard or the shells will fall off during the soak.

Put the eggs and all the rest of the ingredients (including the water) into the Tatung inner pot. Add one cup of water to the Tatung outer pot and steam for about 30 minutes. Let cool, then put in the fridge to marinate overnight. If you aren’t using a Tatung steamer, you can simply do this in a saucepan on the stovetop.

The next day strain the marinade (which can be saved if you want to use it again). Peel the eggs and serve as a snack on its own or as a side dish to a larger meal.

Note #1: it’s ok for the tea leaves and spices to float free in the marinade, but if you prefer, tie them up in a cheesecloth.

Note #2: if you really can’t embrace the chalky yolk, you can simply soak your soft-boiled, cracked shell eggs in a brine for 24 - 48 hours in the fridge. Just be sure to simmer the brine for a few minutes first so the tea will properly brew, then let it cool down before you introduce the eggs.

Ok, a Few More Soy Sauces

Yu Ding Xing soy sauces have been core to our collection since year one, and I’m excited to finally expand the line with a few more classics. For a quick rundown on the entire collection, check out this informational page, which outlines everything from the difference between soy sauce and soy paste to what to use where and for what.

Spicy Soy Paste

We’re finally introducing Yu Ding Xing’s Spicy Soy Paste, one of their oldest formulations. It’s a kicky take on a Taiwanese classic condiment infused with heaven-facing chili powder. I think it tastes like molasses and gochujang with notes of bell pepper.

Use it as a glaze, dip, or drizzle. Personally, I love to toss it with boiled noodles and sesame oil as a base sauce, then garnish with fried egg (or tea egg), and some blanched veg.

Sugar-Free Amber River Soy Sauce

We also are now offering a sugar-free version of Amber River, Yu Ding Xing’s single-origin finishing soy sauce—a malty, chocolatey number.

Usually, Taiwanese soy sauces have a little bit of sugar to balance the saltiness and caramelize during cooking. Though we wouldn’t describe the original as sweet, we’ve brought the sugar-free version in by popular request for those who are limiting or eliminating their sugar intake. Everything else about the sugar-free version of Amber River remains the same as the original: just single-origin Taiwanese black soybeans (Tainan #5), salt, and water. No yellow soybeans and no wheat, which makes this soy sauce gluten-free.

Tatung Steamer Miniature

The limited edition Tatung Steamer Miniatures are back! Tatung Taiwan only makes these once every few years, and we regret to inform you that this will be the last run. After this batch sells out, you won’t see them again. Except maybe on ebay.

While they are not electrified, they are food safe and you can steam with them. The inner lining is a 1-cup removable stainless steel vessel that can be used as a ramekin for small dishes—like steamed eggs—in a full-size Tatung or stovetop steamer. The 6-cup fits three ramekins and the 11-cup fits four.

You can also use them as storage boxes for small household or pantry items. Great for spools of thread, broken up garlic cloves, guava candies, spare buttons, or even leftover NTD and Easycards 悠遊卡.

We’ve had one in our store since opening day, and it's one of the most requested items. Even Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-Wen pointed it out when she visited.

Before signing off, I have to mention that the world feels like a darker, more unpredictable place than I’ve experienced in this not-all-that-short life. I’ve been encouraged lately by the memory of and advice from an old friend. Value what is essential, flout all other conventions, be kind and loving by nature, and nurture a healthy relationship with nihilism (yes). We matter, but our egos don’t. Take the opportunity to do what’s right. Resist in all the small and big ways.

For me, our community provides energy, comfort, and hope. I hope you’ll come see us at the Taiwanese American Cultural Festival in San Francisco on May 10th, kicking off AAPI month. We’ll have Taiwanese dried fruit, Taiwanese jams, and mini Tatungs, and more importantly, are looking forward to meeting with you and chatting about all things Taiwan and the current moment.

If you’re in New York, please join us at our annual seedling sale, spearheaded by Asian-woman-owned farm Choy Division at our shop on May 10th. There’s nothing quite like a bunch of Thai basil growing on one’s windowsill.

And finally, stay tuned for Passport to Taiwan in NYC on Memorial Day weekend in Union Square. It’s the Taiwanese-American festival of the year here in the city.

Wild and crazy like a monster,

Lisa Cheng Smith 鄭衍莉

Written with editorial support by Amalissa Uytingco, Jasmine Huang, and Lillian Lin. Photos and typos by me unless otherwise credited. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please share it with friends and subscribe if you haven’t already. I email once a month, sometimes more, sometimes less. For more Taiwanese food, head to yunhai.shop, follow us on instagram and twitter, or view the newsletter archives.

黑豆油: Everything I Know About Taiwanese Soy Sauce, Part One

A deep dive into the fine and funky world of Taiwanese soy ferments.

清明平安 A Recipe for Qing Ming Jie

Our very first newsletter, featuring the soy sauce documentary we made with Steve Chen.

大同電鍋: Taiwan and its Steam Cooker

All about the Tatung, and its history as a domestic revolutionary.

Love that you've been hitting the books to uncover the history of these ingredients. I also did the same recently for a deep-dive into tofu.

P.S. Wow, you can even donate blood at a 7-11? How does that work?