This is Yun Hai Taiwan Stories, a newsletter about Taiwanese food and culture by Lisa Cheng Smith 鄭衍莉, founder of Yun Hai. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, sign up here.

Happy AAPI Heritage Month—that special time of year when all Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders get a lot of rest and are fed grapes by the pool. Just kidding, it’s the month when we run amok with events and shoutouts and hyperactive cultural joyriding and collapse into a heap sometime after Dragon Boat Festival.

This week, I have the pleasure of writing about one of THE foundational cooking techniques of my Taiwanese-American experience: lu wei, aka soy-braising. The technique is a simple way to transform everyday ingredients (like tofu, eggs, daikon, and beef shank) into something magical, by soaking them in a rich, herbal, soy-based brine. Some of these master brines, or stocks, are kept in constant use for decades, refreshed and matured by constant use.

The secret to starting one is a packet of spices and herbs, known as the lu bao (or “soaking packet”). This little envelope of bark, roots, and dried fruits is the progenitor of one of the most magical potions out there. And we’re excited to be launching the most fragrant one we can find: a thirteen spice braise pack from the mind of Taiwanese food writer Joe Deng. To make it easy for you to start your own master stock, I’ve included a starter recipe and a bundle featuring the other key ingredient: Taiwanese soy sauce.

Make your way to the very end for our AAPI Month roundup, including a giveaway with Real You Mandarin, a save-the-date for an in-store book launch, and details on this year’s Passport to Taiwan festival.

In the most recent episode of our Taiwanese cooking show, Cooking With Steam, I make Taiwanese beef noodle soup in nothing but a rice cooker, which involves the use of a five spice braising pack. There’s a segment where our producer Sam asks me what the five spices are. I get flustered and name many more than five spices, and get many of the so-called non-negotiable ones wrong.

Watch the segment below:

After this moment on set, I immediately thought of my friend Trigg Brown, co-owner of Taiwanese-American restaurant group Win Son, who paused when asked by rapper and food personality Action Bronson to name the five spices on camera. Trigg mentioned to me he was also flustered, despite working with five spice every day.

Maybe we need a mnemonic for it, like “Never Eat Soggy Wheaties,” but instead for “cinnamon, Sichuan peppercorns, star anise, fennel, and cloves.” CPAFC. Crazy Party at Frank’s Crib?

(This isn’t the video in question, but here’s a nice spot with Trigg on Action’s cooking show. Props to Trigg for his performance. I don’t think I could ever let anyone smother a fan tuan in melted cheese in front of me without involuntary side eye.)

As seasoned chefs with a tight focus on Taiwanese foods, five spice flubs might seem a bit embarrassing, but practically speaking, it’s evidence that cooking doesn’t need to be prescribed. When making braises that call for five spice, the basic set is almost always augmented with others, chef’s choice. Five spices become seven, eight, thirteen. I think that’s why it’s difficult to remember; the definition of five spice is actually to riff on it a bit.

Five is a foundational number in Taiwanese and Chinese culture, from the five elements that guide Chinese astrology—Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal and Water—to the five flavors 五味 of Traditional Chinese Medicine—sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and spicy. The number five isn’t really here to indicate the quantity of spices, but the figurative harmony of the flavors therein.

The transformative power of these spices, most often used in the context of braises and stews, is best captured in this charming description of the lu wei 滷味 soy-braising method in Taiwan Panorama, my favorite not-entirely-independently-minded-but-rigorous-nonetheless Taiwanese cultural magazine:

Anyone who has been an overseas student probably has had this experience: go to a butcher shop and buy a bag of cheap chicken, duck, beef, mutton, pig feet, wings, and internal organs that foreigners don't like. Blanch them with boiling water, and then throw them all into a pot of dark marinade, simmer over a low fire, and the aroma will overflow. Not only do the Chinese regard it as a delicacy, but foreigners who don't know the truth can't help but ask for a piece to taste. In this way, you take care of both your wallet and nutrition, as well as substance and appearance.

當過留學生的人大概都有這樣的經驗:到肉品店裡買回一大袋老外不愛、價格便宜的雞鴨牛羊豬的腳、翅、內臟,用滾水燙過以後,再一股腦丟進一鍋黑黝黝的滷汁中,細火慢燉幾小時,肉香四溢,不但老中視為珍饈,不知情的老外也忍不住討塊嚐嚐,於是荷包、營養兼顧,裡子、面子兼顧。

Couldn’t write a better sell, as far as I’m concerned, except that I think some “foreigners” might know the truth nowadays. They go on to say:

For that pot of "transforming the throwaway into the magical" braising sauce, besides soy sauce, the most indispensable ingredient is also a small white cloth pouch called "five spice."

那鍋「化腐朽為神奇」的滷汁原料,除了醬油之外,最不可或缺的,還有一個小小的白布囊,喚作「五香」。

It’s true, there’s really not much more to it than that: a little pouch containing bits and pieces of dried bark, leaves, roots, and fruits.

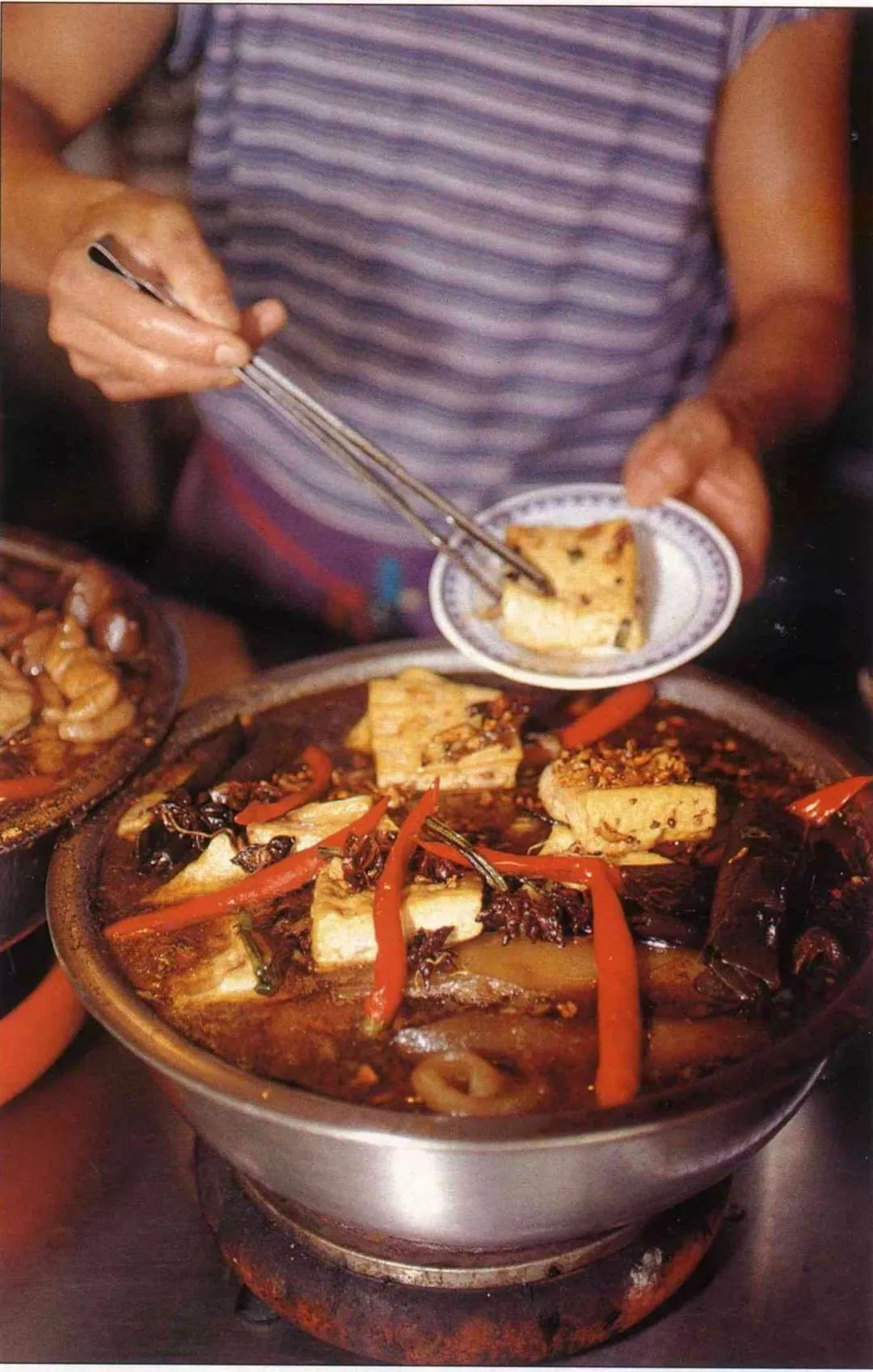

These unassuming, magical little herbs are also the foundation of an entire industry of lu wei food stalls, a key pillar of the Taiwanese weeknight dinner. These proprietors usually have a big pot of master stock going, in which they’ve braised all manner of things—from kelp to dried tofu to pork feet—and laid them out on a rack. Customers pick and choose a variety of braised items, which are packaged up and then eaten on stick. Heaven in a plastic bag, transforming the plain into the magical.

Introducing the Thirteen Spice Braise Pack

We’ve brought in what we regard to be the best little pouch of dried plant parts that we could find. This one’s got a cult following in Taiwan (multiple people have come into the store looking for it), and was developed over ten years by Taiwanese food writer Joe Deng 鄧士瑋 of Foodie Goodie 食貨志.

Like five spice, thirteen spice is also a thing. And, like five spice, the number doesn’t… actually mean thirteen. It’s a numerological metaphor for a spice pouch of limitless variety.

I love this description from A Dragon Chef (which incidentally is a great blog about Chinese food, weaving concepts like solar terms in with traditional recipes):

Same to Five Spices, Thirteen Spices does not restrict to just thirteen ingredients, very often there can be more than twenty ingredients to create a Thirteen Spices mix. It is like an upgrade version of Five Spices, meaning it has a deeper, profound flavor profile. Thirteen Spices has similar function as Five Spices, but it works better to remove stronger odor from meat such as lamb or deer, or for a cuisine that requires stronger seasonings e.g. a Sichuan spicy hot pot.

Deng's journey to create this combination of spices began by trying to resurrect his late father's braised dishes. He found that commercially available braised packets lacked flavor (so agree), and began to research the origins of the spice mixes in old Chinese texts and cookbooks. Thirteen spice is a combination commonly found in Sichuan cuisine, which employs one of the largest varieties of spices in Chinese regional cooking. He explored this concept and tweaked it with help from fans on food forums.

After developing the recipe, it became a cult favorite, and he wrote a cookbook on thirteen spice braising. This spice pack was originally a giveaway to purchasers of that book, but became so popular that it’s now being regularly requested at a tiny Taiwanese general store in America.

In addition to Crazy Party at Frank’s Crib, this spice packet features ginger, sand ginger, galangal, black cardamom, regular cardamom, bai zhi, nutmeg, tangerine peel, cumin, bay leaf, licorice, and sha ren.

Some of these spices are difficult to find in the US. I hoard sand ginger in a jar in the back of my pantry because it’s so hard to come by.

Here’s a brief introduction to some of the lesser known spices included in this lu bao:

Galangal 高良姜

Commonly used in cuisines across Southeast Asia but, in my opinion, not as well known to me as a Taiwanese home cook in the US. It’s a relative of ginger and turmeric, and introduces a citrusy, pine-like flavor.

Sand Ginger 沙薑

A type of galangal and a cousin of ginger, this root has a peppery, camphor-like profile that creates a clean, bright taste. I once wrote a Taiwanese pork cutlet recipe for Bon Appetit and insisted they let me leave this one in, despite almost total lack of availability.

Sha Ren 砂仁

Another fruit in the ginger family (are you noticing a trend) that’s dried and used in Chinese traditional medicine to sooth digestion. It adds a pungent, bitter, aromatic flavor that brings sophistication to the whole shebang.

Chinese Black Cardamom 草果

A large seed pod related to cardamom (which by the way is also related to ginger) that’s dried over smoke and brings a rich, peaty flavor.

Bai Zhi 白芷

The root of Dahurian angelica, one of the most common TCM ingredients I come across on a regular basis other than goji berry. I sort of think of it as “herbal Tylenol,” as in, “Feeling unwell? Make bai zhi tea.”

Lu Shui Master Stock Recipe

The key to good lu wei is all in the master brine, or lu shui 滷水, which translates literally to soaking water. A high-salinity, aromatic brine imparts not only the right balance of flavors, but also a perfect deep brown color. Some lu wei shops are known for lu shui that, like a sourdough starter, might be 100 years old—constantly heated, refreshed, and matured.

Ingredients

2500 ml of water

275 ml of Vat Bottom Soy Sauce

50 ml Taiwanese rice wine

50 g rock sugar

6 cloves garlic

4-6 whole scallions, broken in half

1 big thumb of ginger (2-3”) smashed (or sliced, if you don’t have anything good to whack it with)

2 lbs beef shank, chicken parts, or pressed tofu

Instructions

Bring water to a boil.

Add in both soy sauces, rice wine, rock sugar, garlic, scallions, and the braise pack. Lower to a simmer.

Introduce whatever ingredients you want to braise, and simmer until tender. Try to keep to the same type of ingredients to be able to control cooking time (i.e. don’t cook chicken parts and beef shank at the same time). A general guideline might be twenty minutes for tofu and up to a couple hours for a large shank.

Braised foods, once tender, can be served warm, but it’s much better to let the braised ingredients cool down in the stock. This allows them to “plump” back up by reabsorbing liquids and salt. In fact, the name “lu” 滷 refers to this soaking step, and not the simmer.

When you’re done using it, bring it to a boil, strain it, and freeze it. Use this as the foundation for your next stock. A good lu stock is flavored by all the things that have come before, so enjoy building the complexity.

To serve, slice the braised ingredients into chopstickable slices, arrange neatly on a platter, and top with cilantro, if you swing that way (I do).

Lu Wei Bundle

To help you get started, we’ve put together everything you need for a bangin’ pot of Taiwanese master stock.

This bundle contains the thirteen spice braise pack and two kinds of soy sauce we recommend for making a great lu wei master stock: Vat Bottom Soy Sauce for its high salinity and rich body, and Caramelized Sugar Soy Sauce for its rich caramel scent and its ability to impart color on the braise.

Dip your braised meats and proteins in the sweet and mildly hot Spicy Soy Paste, also included, for the finishing touch.

It’s AAPI Heritage Month!

On Saturday, May 17th from 5-9pm, we’ll be at The Center’s AAPI Food Festival with dried fruits, and Taiwan Pride merch (flags and pins). Hosted by Miss Ma’amShe with DJ Michele Yue, the food vendors at this festival include some of our favorite LGTBQ+ AAPI businesses, from Bánh by Lauren to Jessie Yuchen.

Real You Mandarin, an online Chinese language curriculum for ABCs, ABTs, and advanced Mandarin learners, recently launched their new course “Real You Mandarin: Self-Expression.” Designed to help you navigate conversations through some of life’s most complex intersections, modules cover topics like expressing your feelings, parenting, and caring for aging parents. Use our discount code yunhai10 for 10% off either the first module as a standalone purchase or the full course pre-order.

Taiwanese menswear brand a/c space launched their A Place We Call Home T-shirt, which features symbols and everyday objects that remind the founder of her roots and childhood—things she believes many others will recognize and resonate with. The rice cooker that always sits on the kitchen counter, the sound of mahjong tiles being shuffled, and pineapples, a nod to the farms where her mother grew up. It’s a design that speaks to the shared, familiar feeling of home. These are also available in our brick-and-mortar starting this weekend!

In celebration of Taiwanese and Taiwanese-American heritage, Passport to Taiwan will return to NYC on Sunday, May 25th at Union Square from 12-5 pm. We’ll have a booth there with dried fruit, Taiwanese jams, Tatung miniatures, and a very special something that will be announced soon!

Save the date for Thursday, June 5th: We’ll be hosting a party to celebrate the launch of Makan’s TAIPEI by Ibi Ibrahim, the store’s third anniversary, and Dragon Boat Festival. More details to come.

And if you haven’t seen it, we released a tiny little epi of Cooking With Steam, demonstrating how to cook rice in a Tatung. The final and most exciting episode of the season is coming soon: Cabbage Rice, Pork Rib Soup, and a Storm. Stay tuned.

Crazy party at Frank’s crib tonight,

Lisa Cheng Smith 鄭衍莉

Written with editorial support by Amalissa Uytingco, Jasmine Huang, and Lillian Lin. Photos and typos by me unless otherwise credited. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please share it with friends and subscribe if you haven’t already. I email once a month, sometimes more, sometimes less. For more Taiwanese food, head to yunhai.shop, follow us on instagram and twitter, or view the newsletter archives.